|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sheffield, a city famous for its high-quality specialised steels and the many industries closely associated with them - munitions, general engineering, forgings of all kinds, cutlery, machine knives, springs and numerous hand and edge-tool makers - must also have been something of a centre for small-lathe production. In addition to Portass, Flexispeed, Faircut, Kay, Adept the very rare Bunting was also manufactured - and it is also thought that Samuel Peace & Sons made lathes for sale by James Neil, the latter using their well-known Eclipse label. Later, the tradition was continued by the woodworking-tool manufacturer Sorby who, during the 1990s, produced a top-quality wood-turning lathe (and a range of other wood-turning-related products) in premises not 100 yards from what had been the Portass factory.

Portass lathes date from the very early 1920s and were first badged as being made in the west of Sheffield by "The Heeley Motor Manufacturing Company" and then "The Portass Lathe and Machine Tool Company". Although Sheffield's main heavy industries, and the larger-volume steel plants of Rotherham, lay to the east (and so down-wind of the better-class housing), there had been a long tradition of both large and small-scale engineering (especially edge-tool industries and in particular scythe making and grinding) in valleys to the south and west - using water power from the Sheaf, Porter, Loxley and Rivelin steams. Founded in 1889 by Charles Portass, the original Portass company was concerned with building and constructional engineering but, by the outbreak of the First World War (1914--1918), had evolved to the extent that it was able to take on a variety of government work. Projects undertaken including the usual munitions sub-contracting and, more interestingly, the manufacture of aircraft components such as landing gear parts for Avro, Bristol and Nieuport fighters, seaplane floats for Blackburn and Fairey, tail units for Avro and De Havilland - and even the building of a complete batch of fifty Sopwith Snipes - though no doubt the history of what was built, and when, was suitably adjusted and embroidered by Portass for marketing proposes. In the 1920s, and by now trading under the Heeley name, Portass turned its attention to building bodies for the car, lorry, ambulance and bus markets but, as these had become an increasingly "in-house" activity for the chassis manufactures, Portass diverted into the manufacture of small machine tools for the hobby and light-industrial market.

Following the founder's death in 1924 (and almost certainly at the point where diversification into machine tools was taking place), the business was split between his sons Fred and Stanley. Fred ran "F. W. Portass", a company that concentrated exclusively on tiny lathes and shapers badged as "Adept", while Stanley made only larger machines with his business eventually becoming, around 1953 (or earlier), "Charles Portass & Son". Stanley was based by the river Sheaf in the "Buttermere Works" (the building still stands, in Buttermere Road, off Abbeydale Road, near Millhouses) while F.W.Portass was located in Sellers Street - again off Abbeydale Road, but a mile closer to the city centre. Letters survive showing how, unsurprisingly, the two companies were frequently confused, with mail and personal callers having to be redirected. The Buttermere Works, according to the memories of a visitor who called just before the company closed in the early 1970s, were fitted out with a ground floor holding the heavier machine tools and a mezzanine floor with a collection of various lighter tools, an assortment of ancient fitting benches and numerous surface plates. All the machines employed were entirely conventional: two planers for the lathe beds - one an 8-foot stroke Smith & Coventry the other a smaller machine of uncertain origin - three vertical millers - a large WW2-vintage Brown and Shape and a heavy 12-inch shaper plus a smaller one of Portass's own manufacture - three large and several smaller centre lathes (all driven from overhead-line shafting) and two or three capstan lathes - with one appearing to be permanently set up for turning ball handles and the other dedicated to lathe headstock spindle production. One of the larger lathes had been adapted for the simultaneous line-boring of lathe headstocks and tailstocks by the simple but effective means of a jig mounted on the saddle. Leadscrews and racks, which Mr. Portass said were uneconomical to manufacture, were bought in from the Halifax Rack and Screw Company.

With Mr. Portass in charge of day-to-day production it appears that there was no need for engineering drawings - he kept all the critical dimensions in his head. A gentleman who had worked there as a summer-holiday job during in his late teens, related the story of being given a job to complete on a milling machine. After the initial instructions had been given, Portass then took a stick, drew an outline of the job in the dirt on the floor, appended the necessary measurements and left him to it…

Until the late 1960s there had also been a foundry, almost next to the machine works, allowing the company to oversee manufacture from raw materials to finished product. When the Portass foundry closed castings were sourced from a company in nearby Dronfield. Unconfirmed reports say Stanley was a doctor, involved at one time in optical research, and devoted only part of his time to the company with the help of a small full-time staff - though by the very end, as demand ran down, he was working with just his brother-in-law.

Continued below:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

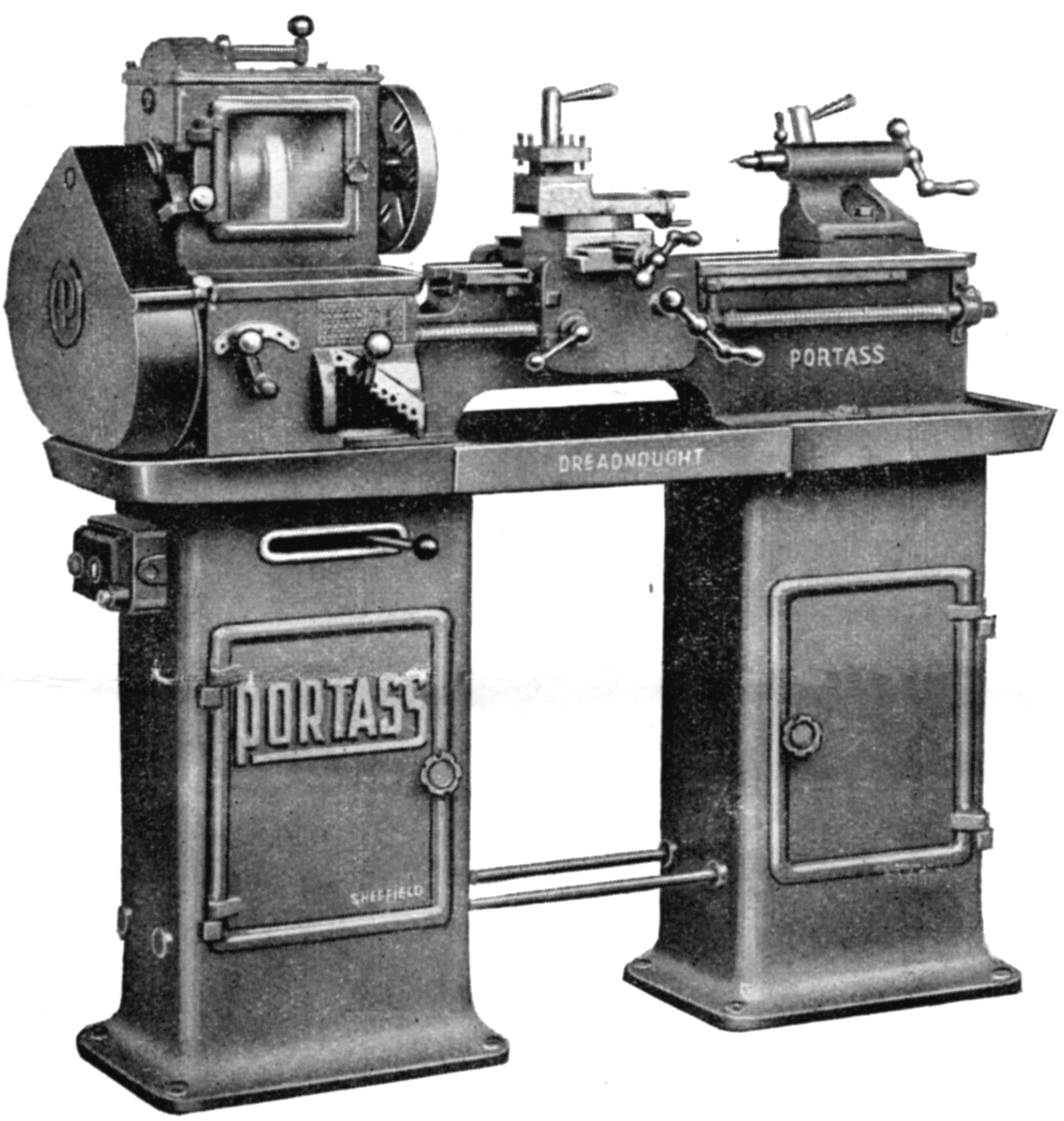

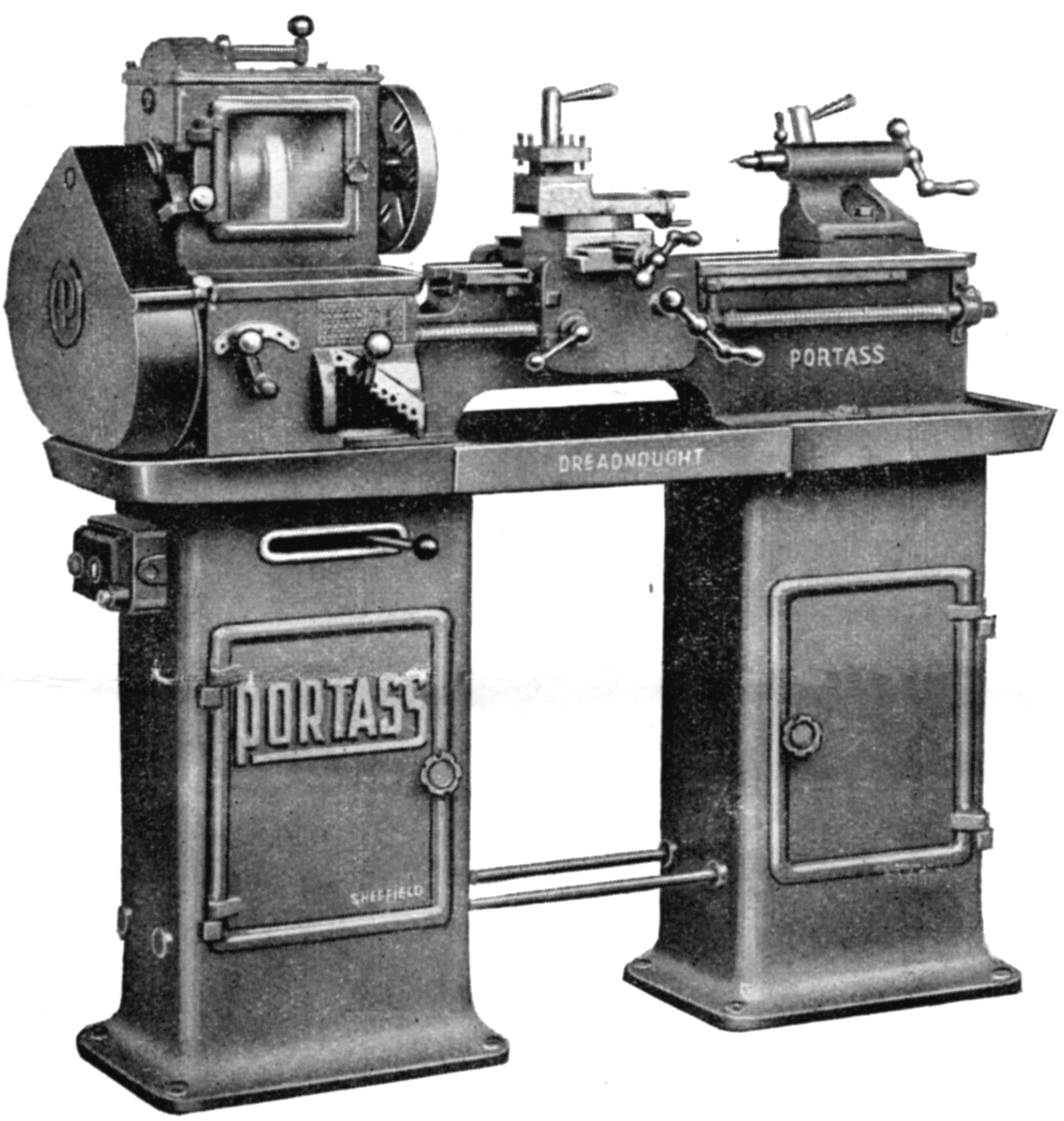

The "Green List" Dreadnought "Floor Model"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Continued:

By the mid 1950s Portass had produced over twenty-two different models of lathe, together with a variety of millers, shapers, drills, countershaft-drive systems, foot motors, vertical-milling slides and T-slotted cross slides. Even in the late 1930s, Mr Portass admitted in one of his homily-rich advertising leaflets that: "It is realised that in offering so many types, we are perhaps apt to confuse you, but we should like you to realise that we have produced such a variety of lathes for many distributors in all parts of the world, that we have built up a range likely to appeal to most classes of user at prices to suit all pockets." In reality, production of all but lathes appears to have been very limited - and even these were made in batches to order with, at any one time, only a limited selection of the range available for immediate delivery. A typical example was the Model "C", a low-cost special sold only direct from the factory, the margins being insufficient to allow any dealer discount. The "C" was a very basic lathe, with a 3-inch centre height, listed in 1953 at £13 : 17s : 6d for the 10-inch between-centres model and £15 : 10s : 0d for the 17-inch. It was supplied without backgear or screwcutting and with the T-slotted saddle carrying just a single, swivelling tool slide. Even with its attractively low price, few can have been sold and the model is rarely found second-hand. Another limited-production machine was a rather different, backgeared and screwcutting model that broke with many Portass conventions; the 4-inch Heavy Duty - only two surviving examples being known. Also seldom found, despite being promoted in (tiny) advertisements in the Model Engineer Magazine during 1954, was the 3" x 12.5" Model L: Backgeared but not screwcutting this is known to have had its carriage driven by hand through carriage rack-and-pinion gearing - and the saddle formed as a T-slotted boring table topped by a single swivelling tool slide. If you recognise this as a Portass model as one you own, the writer would be most interested in making contact.

Portass was also kept busy supplying machines for retailers to re-badge as their own and examples have been found marked: Altona, Amax (the badge stated "Amax Lathe, Russell, Croydon Eng"), A.T.M., B.I.L., Bond's Maximus, British Industries, Calgary Canada, Companion (sold by Johns in Auckland, New Zealand), "Eclipse" (for the Sheffield hand-tool makers James Neil & Sons), Enox for an unknown distributor or retailer, Excell, G.A. (George Adams), Gamages, Graves, James Grose Ltd. of London (the latter chiselling off the Portass name and substituting their own badge), Juniper, Randa, Temmah, Wakefield, Woolner and Zyto, All appear to have been based on established Portass models, nearly always a version of the "Junior" or the venerable "S Type", although in every case some small differences, usually down to cost-cutting, can be found. However, it may be that some examples were not made by Portass, but copied - one Portass advertising sheet claiming: Beware of Imitations. Portass lathes are being systematically copied and marketed and purchases should be careful to ascertain that the maker's label is attached to the machine.

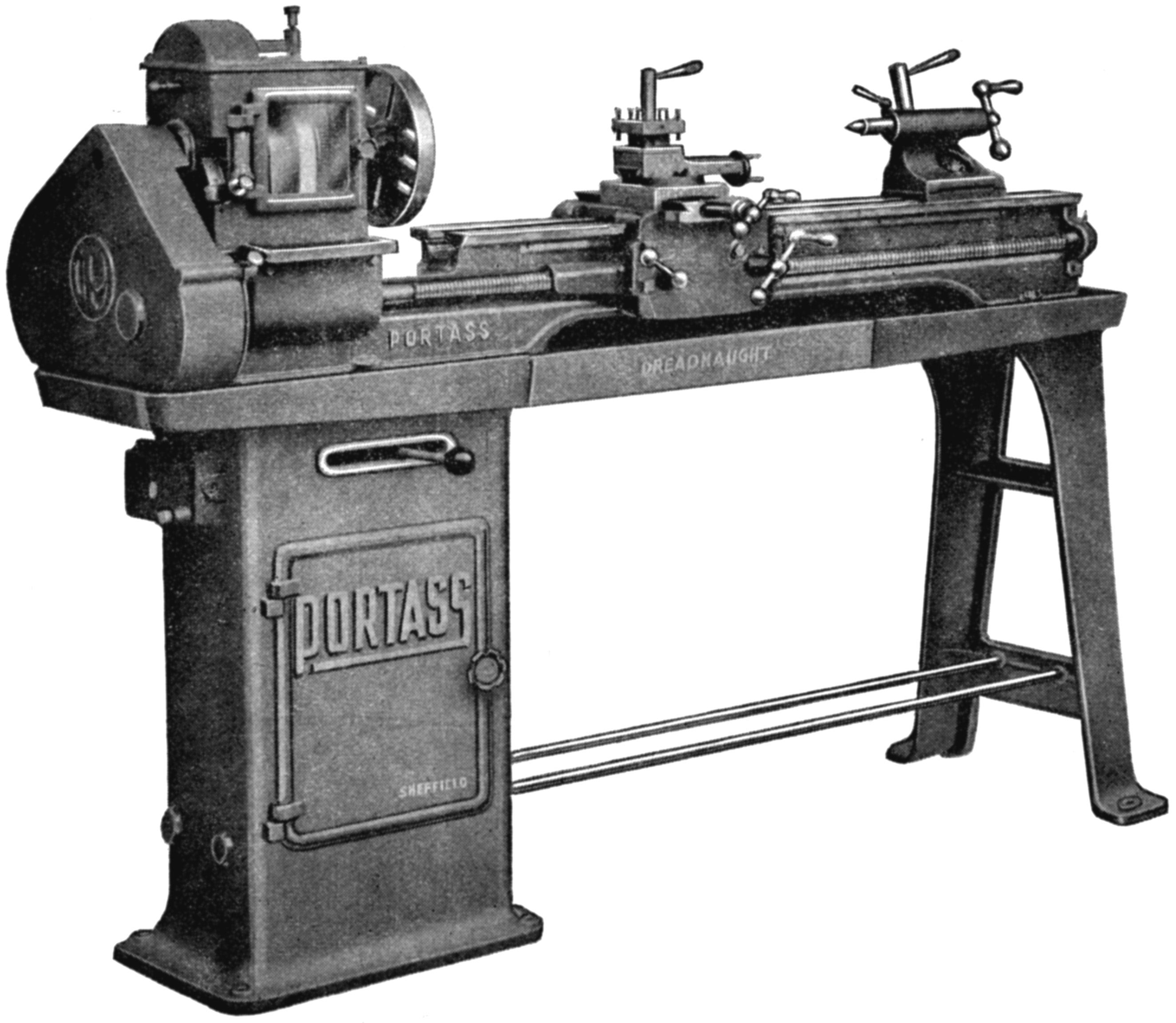

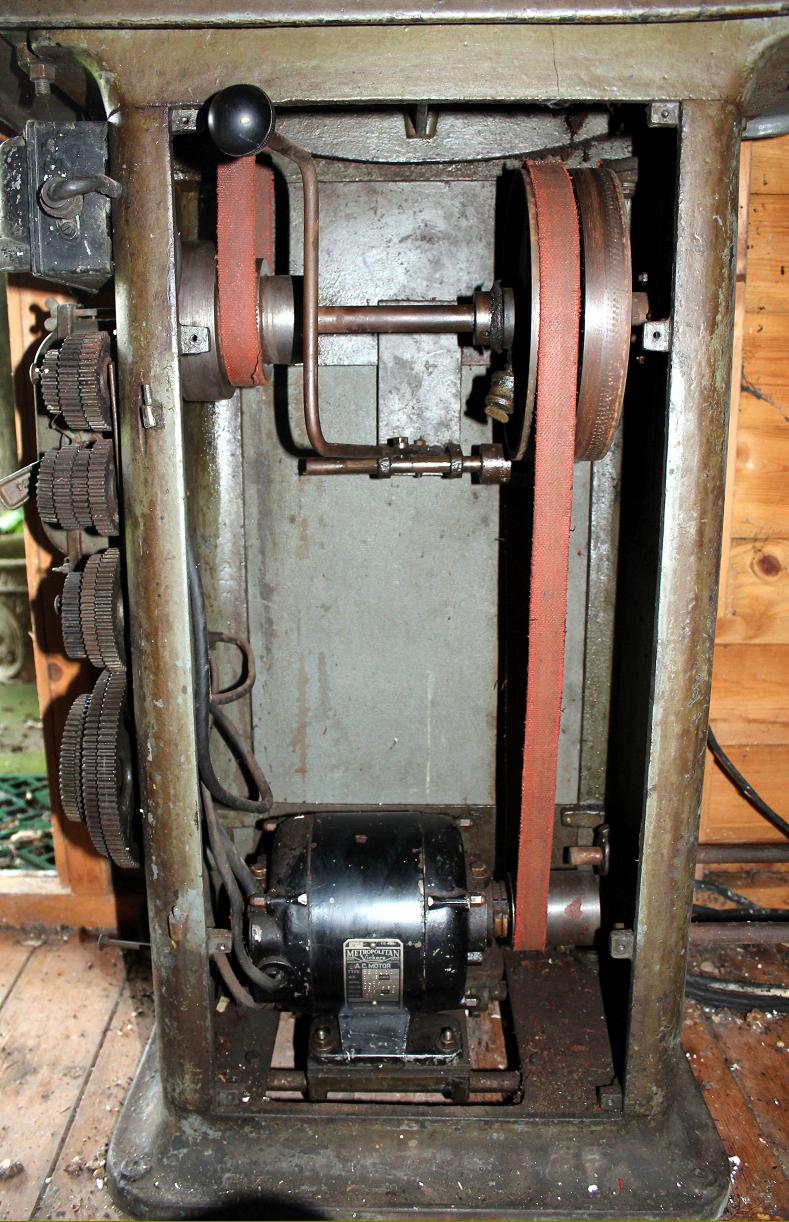

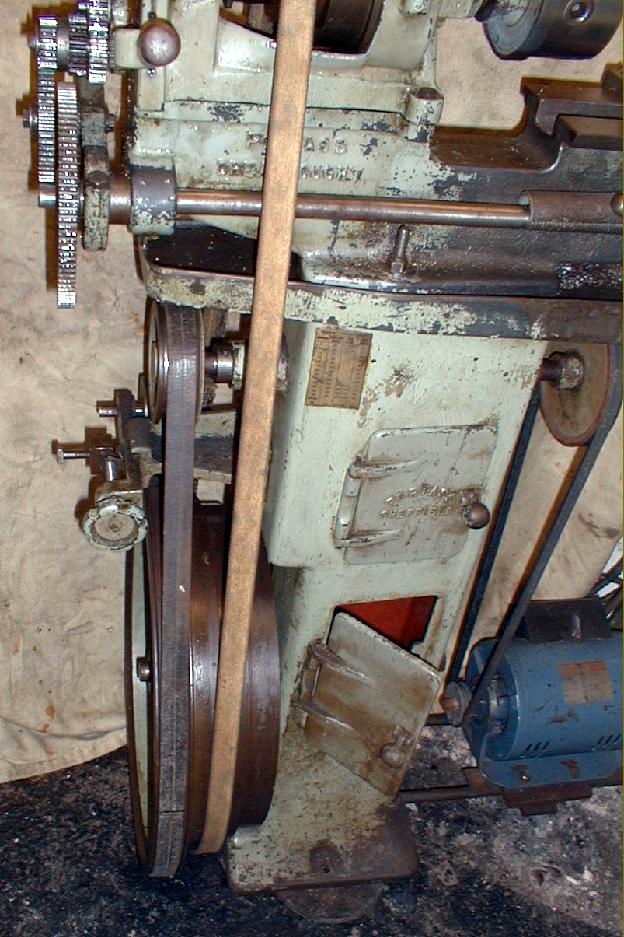

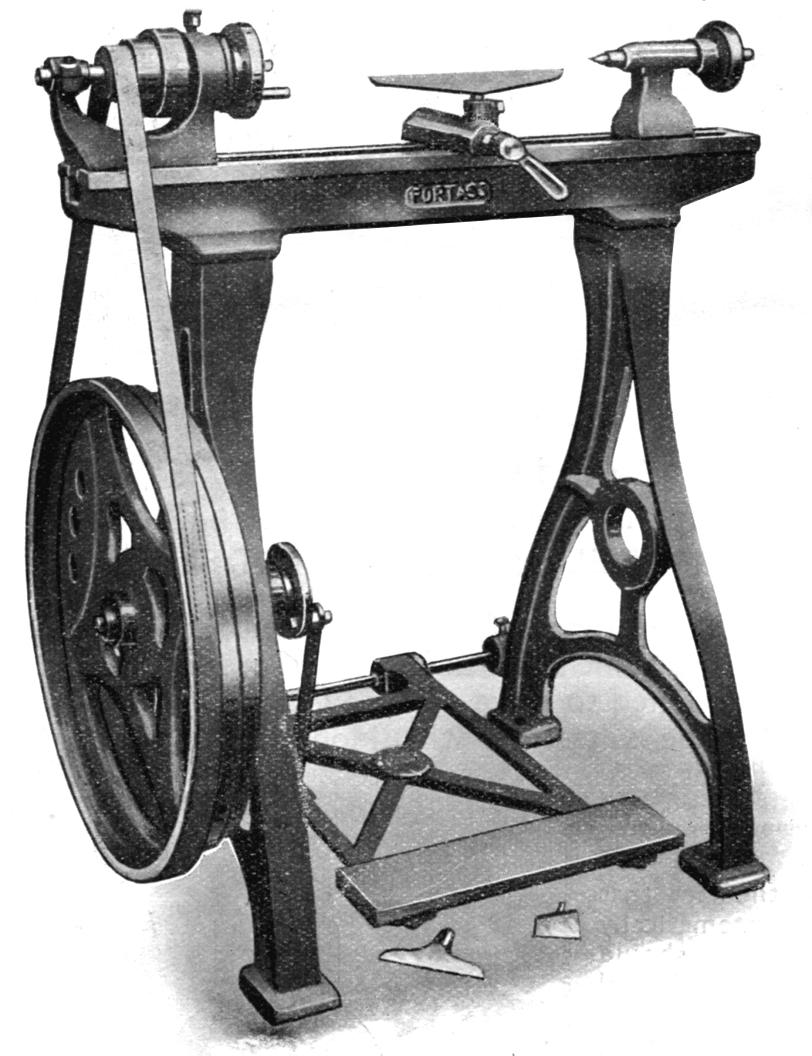

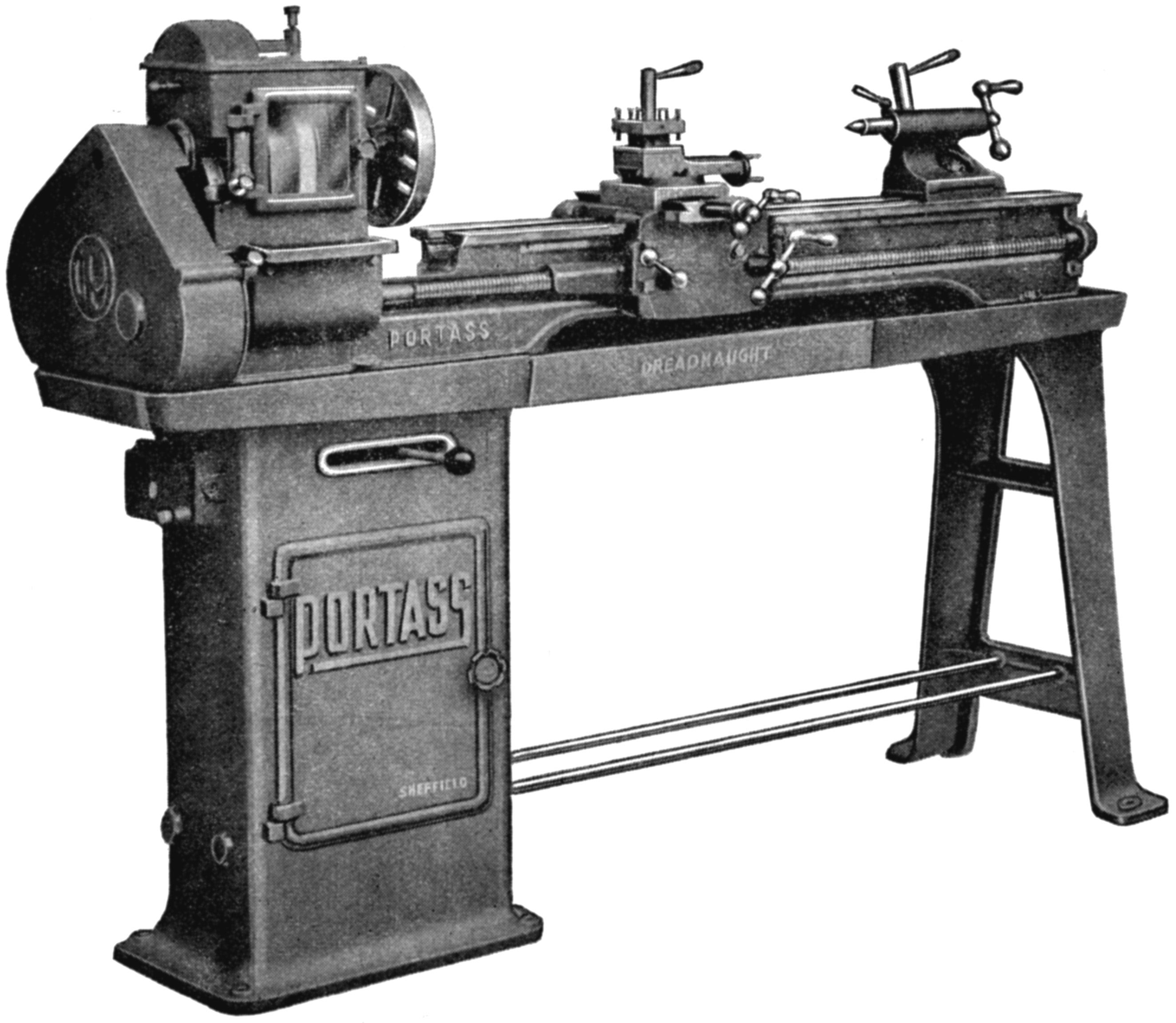

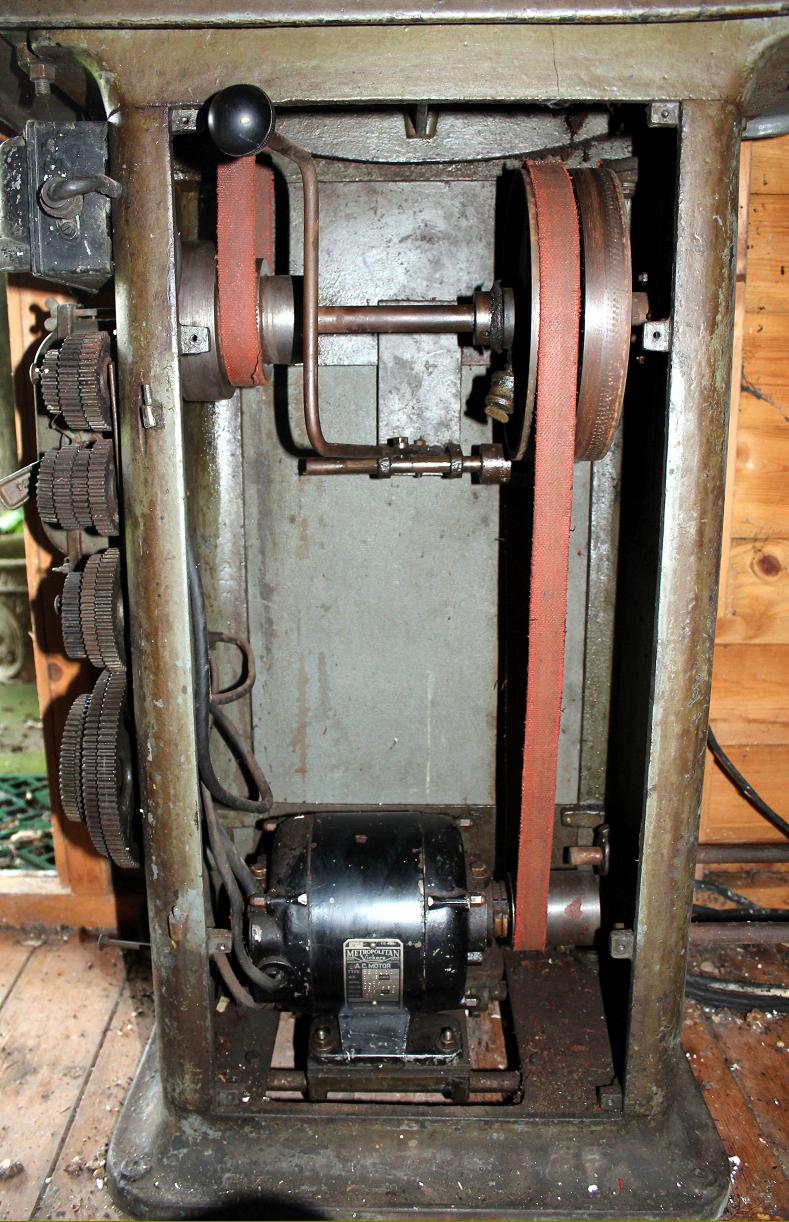

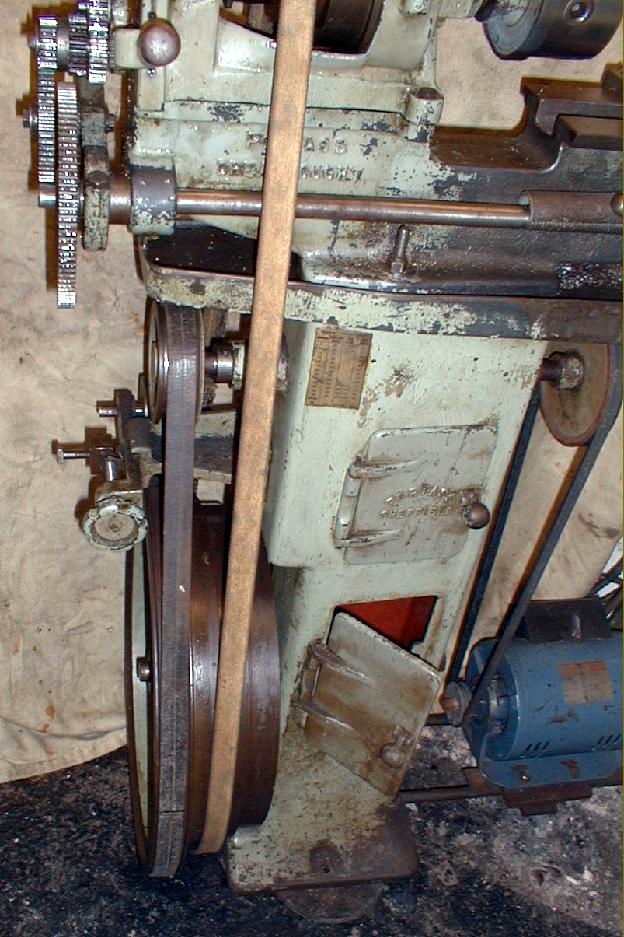

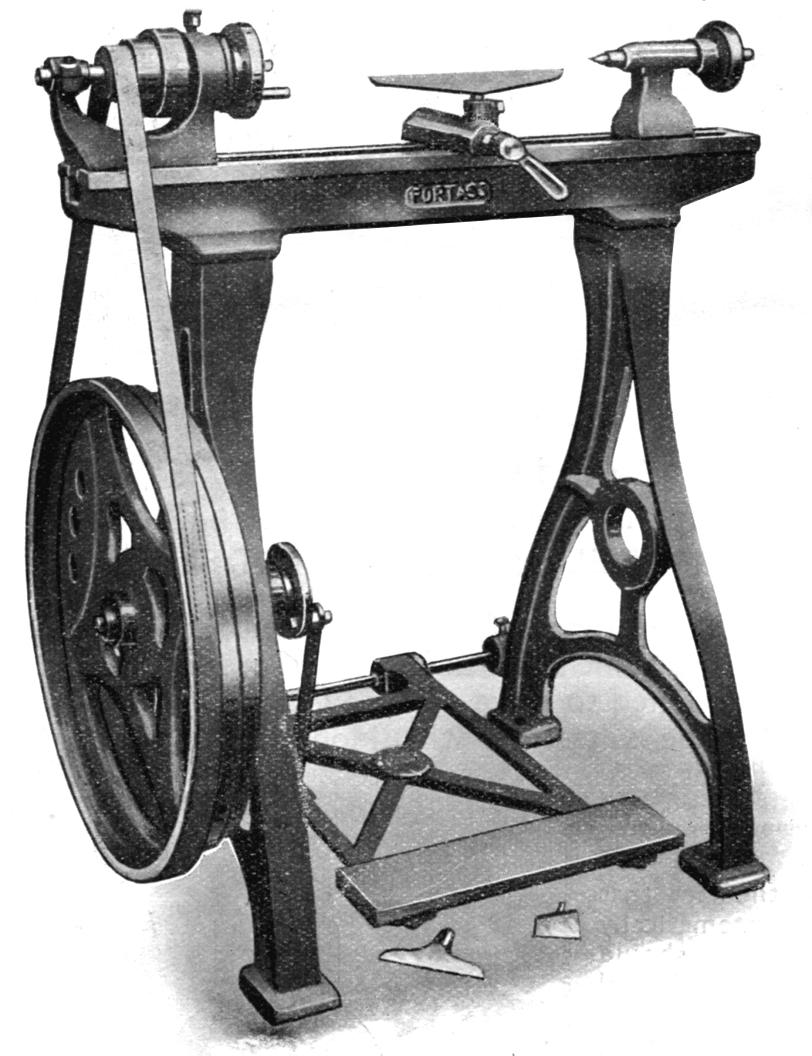

Most famous of the Portass line - though not the best selling - was the popular and long-lived "Dreadnought". Unfortunately (and confusingly) the name was applied to a variety of models but is most commonly found on a heavily-built, 35/8" x 20" gap bed, backgeared and screwcutting machine fitted with tumble reverse and made for both bench and stand mounting. The typical Dreadnought model shown in the first picture below is mounted on the maker's "underdrive stand", and follows the sensible Portass principles of using, wherever possible, very long flat drive belts, in the case over 20 feet of them. However, one dreads to think of the transmission losses as the motor struggled to first spin a plain-bearing cross shaft (through the upper part of the left-hand leg) then a massive, 112 lb cast-iron flywheel and, finally, the strongly-built, bronze-bushed headstock spindle. In reality the machine performed extremely well, and an example used by the writer for a number of months ran with turbine-like smoothness - the flywheel proving capable of storing prodigious amounts of energy. The reasoning behind this design, and for not employing V-belts, was as follows: Short, tight V-belts rapidly promote ovality in the [plain] bearings, lack of resilience in the drive, undue wear and sudden load taking to the motor with a general lack of smoothness and finish to the work. Any old and experienced engineer will concur with this view. Unfortunately, the success of many tens of thousands of American V-belt driven Atlas and Craftsman lathes (fitted with roller bearings) would appear to contradict this opinion.

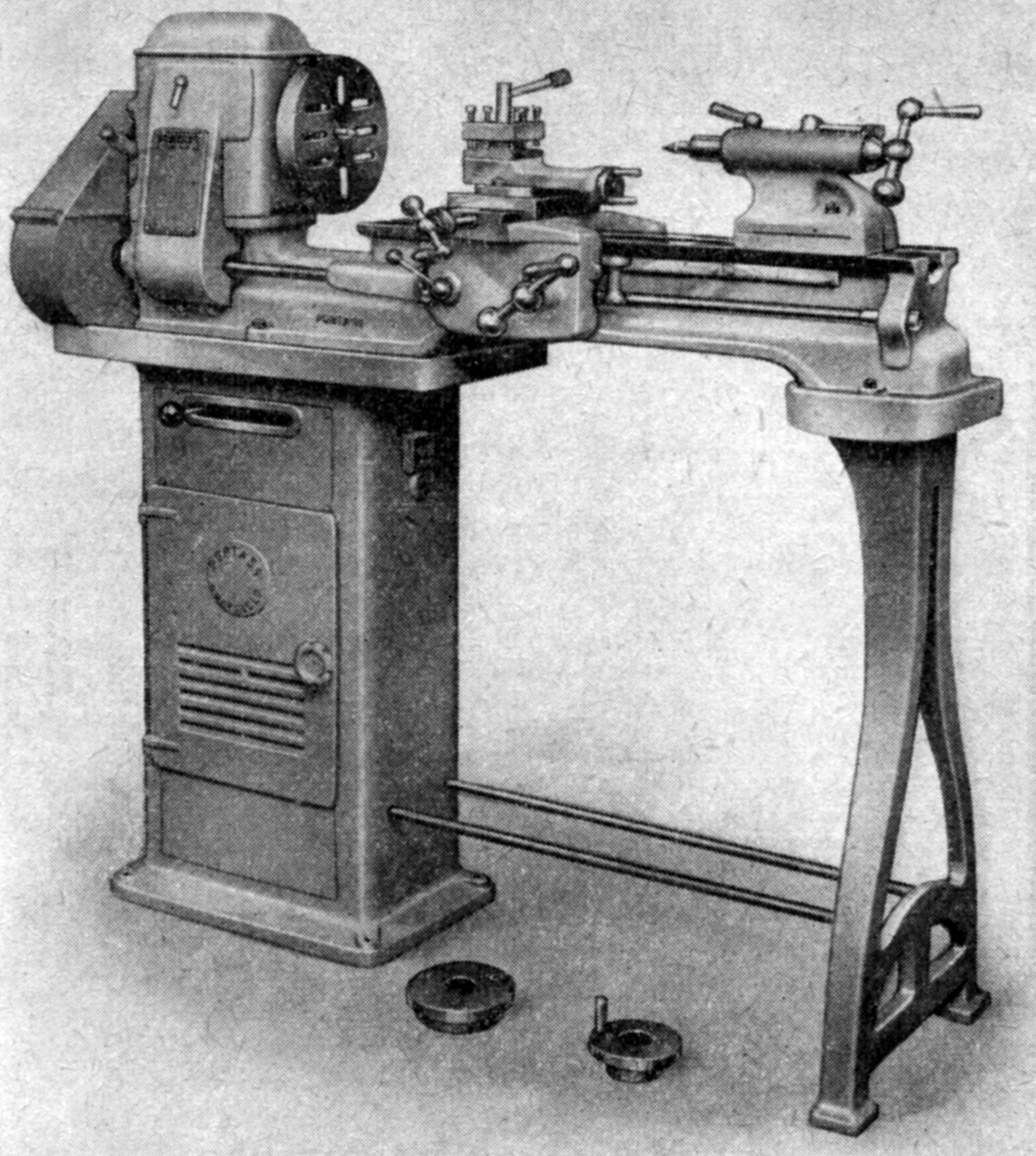

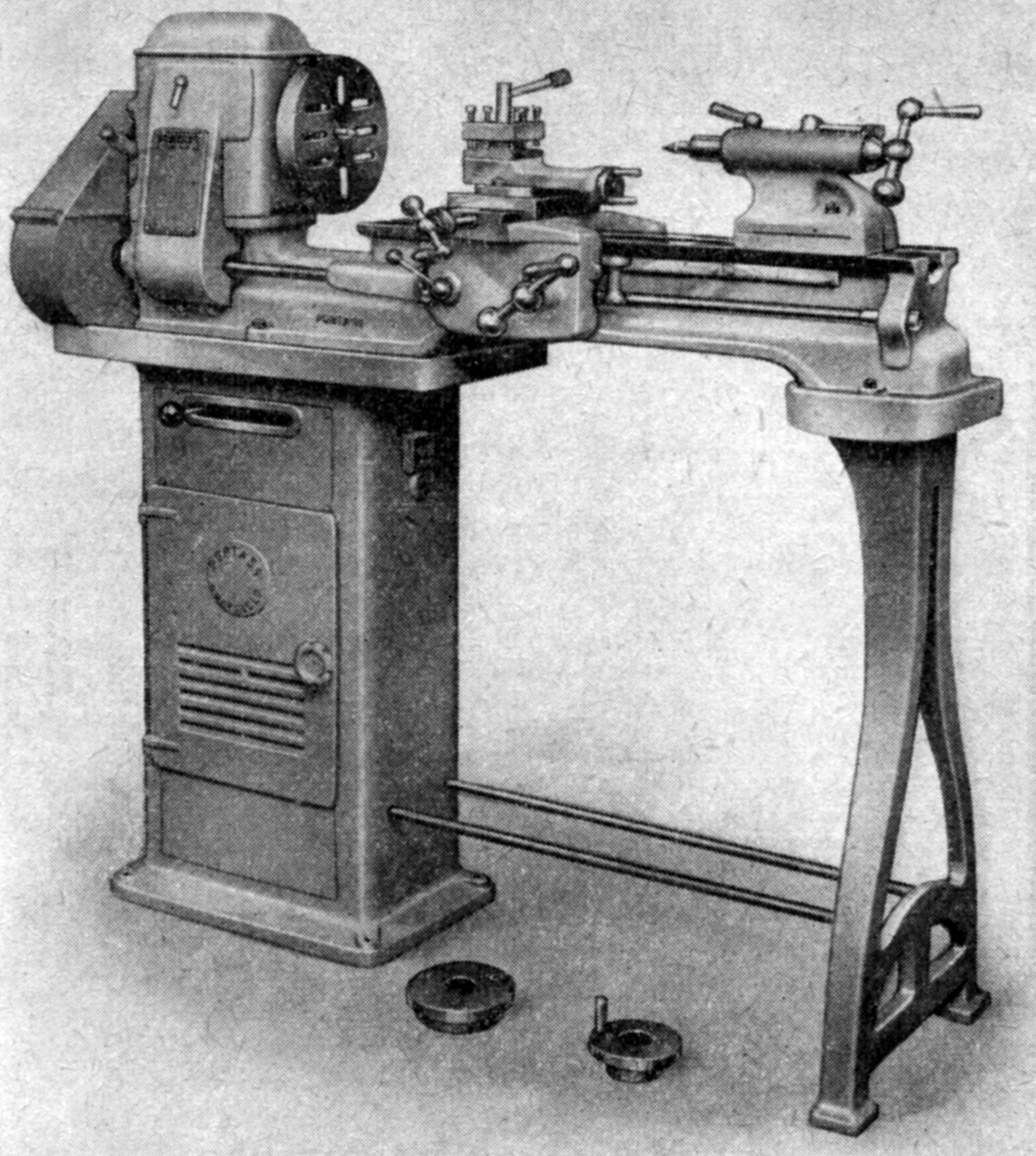

Also shown on this page are very two very rare Dreadnought models with centre heights of 5 and 45/8-inches; it is known that only six examples of the version with a hinged "Perspex" cover on the front of the headstock and a choice of a screwcutting gearbox or chanhewheels were made, and it must be assumed that the other model, the "Big Dreadnaught" with a more conventional appearance and screwcutting by changewheels, was also made in very limited numbers. One additional, infrequently encountered type was badged "Dreadnought Junior" - and seems to have been yet another variation on the ubiquitous "Model S" - though perhaps of a heavier build.

Most of the ordinary 35/8" x 20" Dreadnought models were supplied for both bench mounting and stand mounting first with flat belt drive - listed (for some unfathomable reason) by the makers as "Green List" machines (see illustration below) the only Portass known to have been offered with power cross feed - though the mechanism was Victorian in design with a power-shaft passing down the back of the bed. In the mid 1950s, as demand for the original, now rather old-fashioned looking Dreadnought waned (doubtless under competitive pressure from the success of the very much more up-to-date Myford ML7), Portass introduced the backgeared, screwcutting, 6-speed 35/8" x 17" gap bed D5 or "Dreadnought Five" (not to be confused with the quite different Mk. 5) almost a miniature version of the earlier machine with both headstock spindle and tailstock barrel of 1-inch diameter. The headstock was almost identical to that employed on the last design of "S Type" with a 9 t.p.i x 1.122" spindle thread and 3/8" bore but with tumble-reverse fitted as standard. The lathe was brought further up-to-date by the use of a long cross slide with 5 T-slots, V-belt drive and the complete guarding for the changewheels and backgear fitted as standard. A set of eleven changewheels was provided: 2 x 20t, 25t, 30t, 35t, 40t, 45t, 50t, 55t, 60t and 65 teeth. As is so often the case "new" did not mean "better" and the "PD5" (as it became known) was only a pale imitation of its heavier, more workman-like forebears.

Today the most frequently encountered Portass (and so what must have been the best-selling model and the most often re-badged for sale by others) is the Model S, a simple, 3" x 12.5" lathe with a gap bed and (usually but not exclusively), backgear and screwcutting. Designed in the late 1920s and built until the outbreak of war in 1939, the Model S was re-modelled and brought back into production - "in response to many earnest requests from home and overseas" - in 1951, when it was available with centre heights of 3 and 33/8 inches and between-centres capacities of 121/2 and 18 inches.

At around the time when the D5 was nearing production, the firm suffered an almost terminal blow when a large number of patterns was stolen - so preventing them from supplying spares for the majority of older models. Stanley died in the early 1970s and the firm ceased trading, with all the remaining stock of spares and patterns being destroyed. For many years afterwards the porch of the family home near the works retained its attractive stained-glass Portass logo; sadly this was lost when the house changed hands and, the new owners, not realising its significance, ripped it out. The Portass family appear to no longer have any connection with Sheffield, and if any reader is able to supply additional information about the Portass Company, or the family, the writer, a native of the city, would be interested to hear from you...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

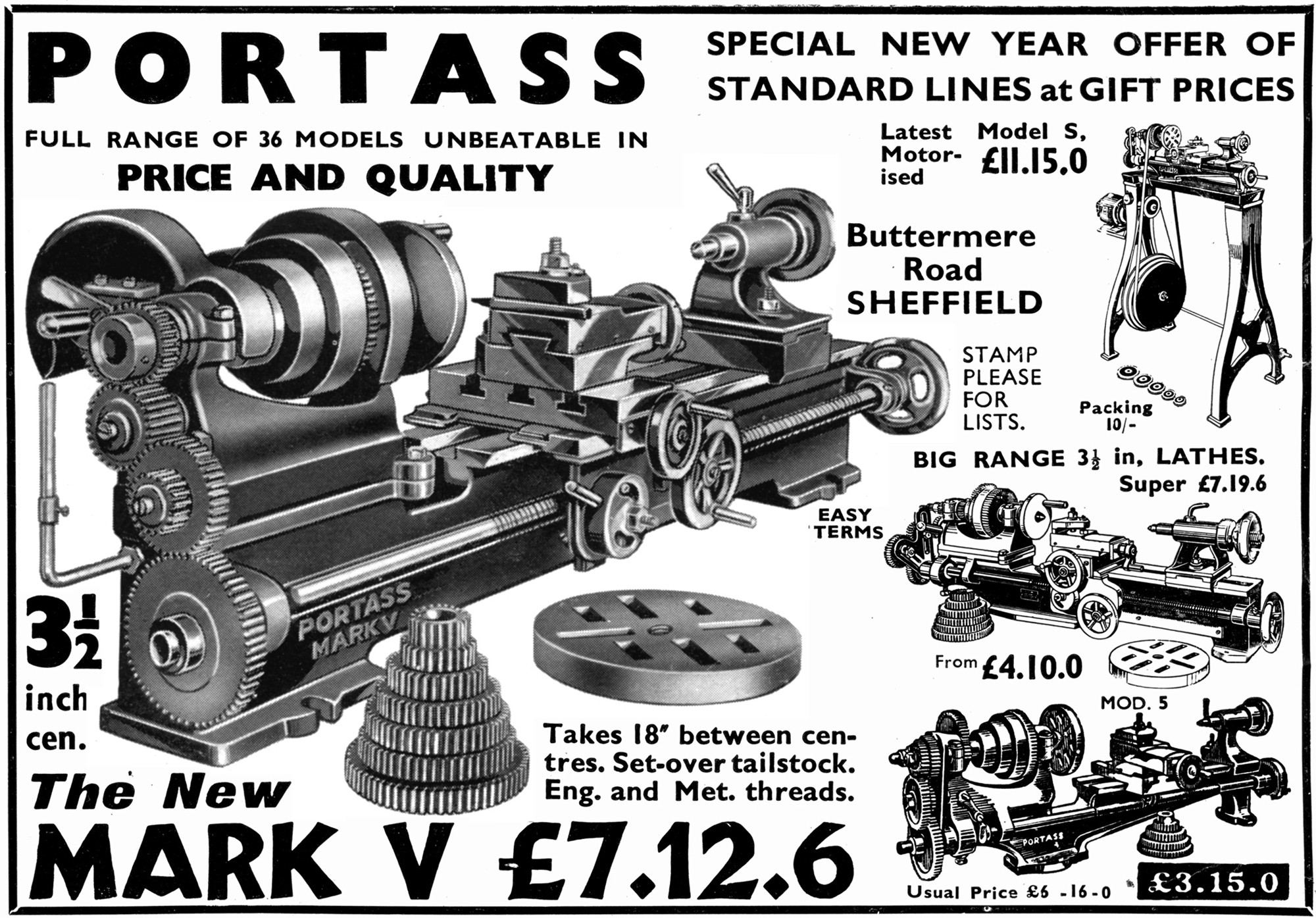

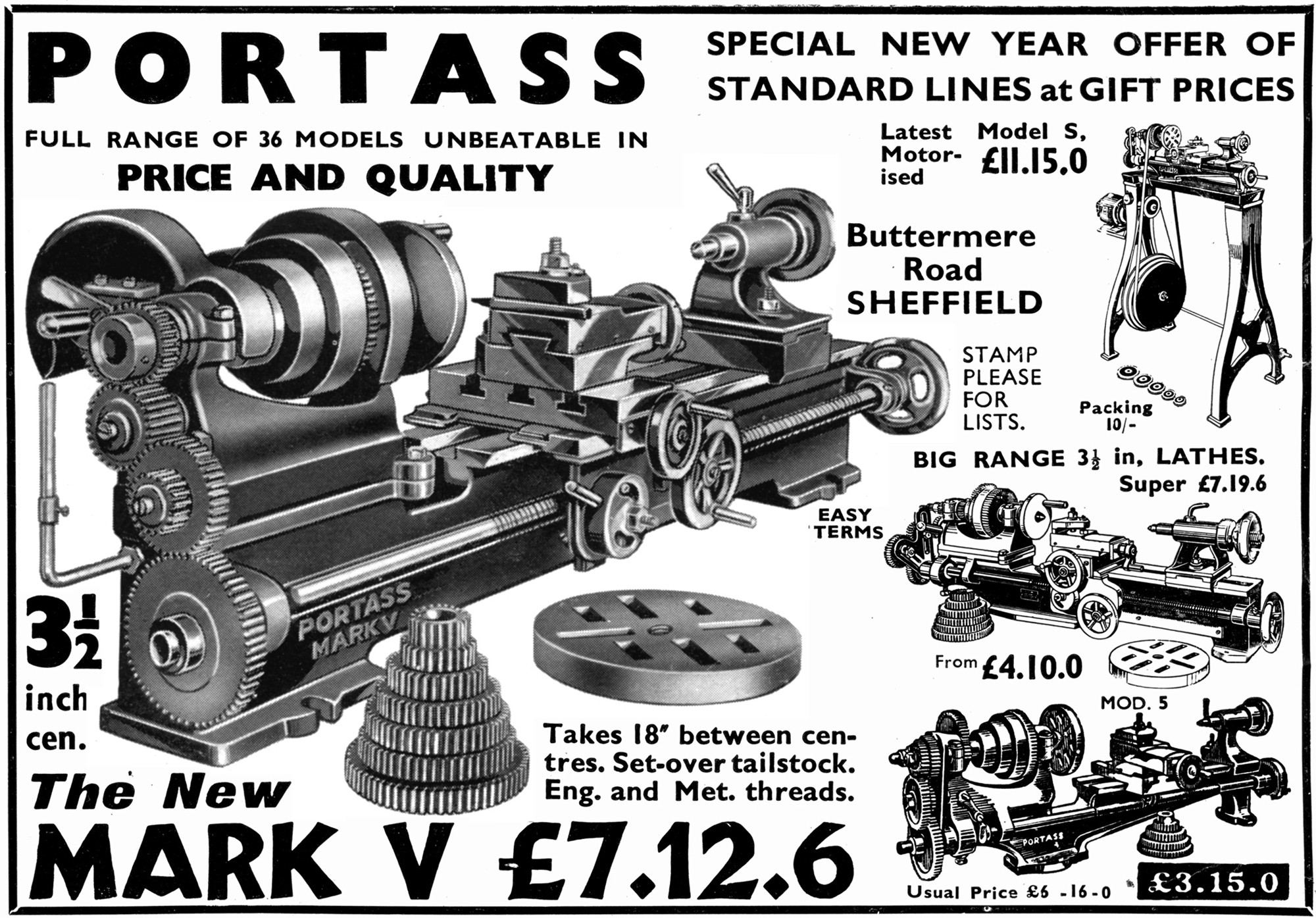

Portass were always careful with their advertising budget, being content with tiny insertions in the model-engineering press and the use of old-fashioned illustrations. It therefore came as something of a shock when, in 1939, they competed with Pools, Randa, Drummond and Gamages with a full-half page insertion. However, this momentary loss of control did not last - for it happened just the once pre-WW2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Original model 35/8"-centre height Portass Dreadnought for bench mounting on a heavy cast-iron chip tray. This version was labelled by the makers as the "Green List S.C. Bench Lathe" and could be had with power cross feed - though the mechanism was Victorian in design with a power-shaft passing down the back of the bed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The largest-ever Portass, also called a Dreadnought, was made in both 45/8" and 51/8" centre heights (only six of the latter being manufactured) and fitted with No. 3 Morse taper tailstock barrel This very rare model was sold exclusively on an underdrive stand and was the only Portass known to have been offered with the option of a screwcutting gearbox and power cross feed - though a version with a lower centre height and changewheels (below) was also listed. The Perspex window in the hinge-open cover on the front of the headstock was surely a unique feature, enabling the fascinated owner to watch in jaw-dropping amazement as the "works went round".

If you have a lathe like this - let's call it the "Portass Window" - the writer would be very interested to hear from you.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Changewheel version of the 45/8" centre height Dreadnought

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

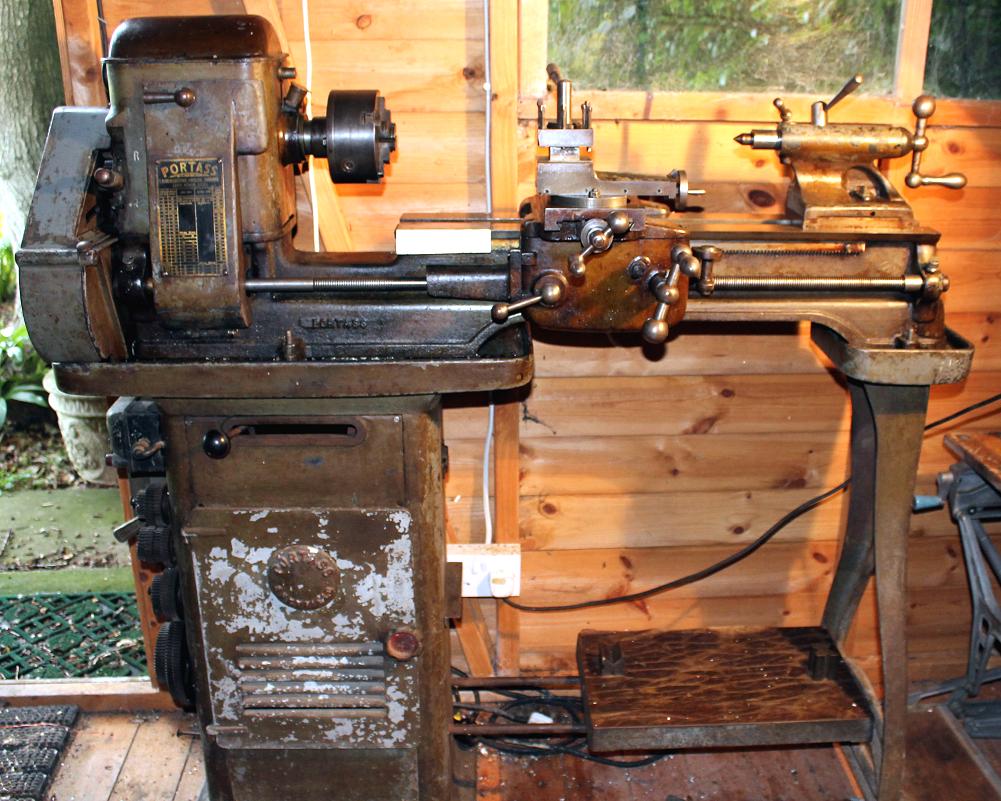

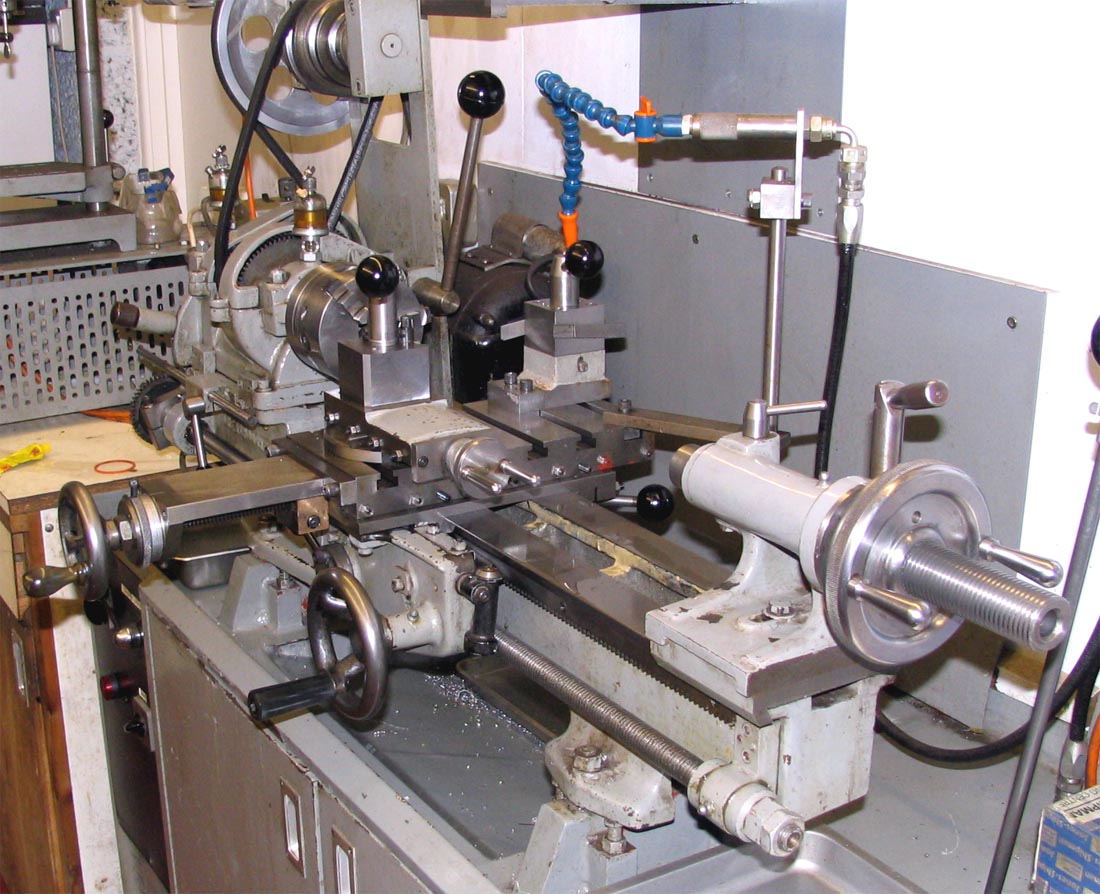

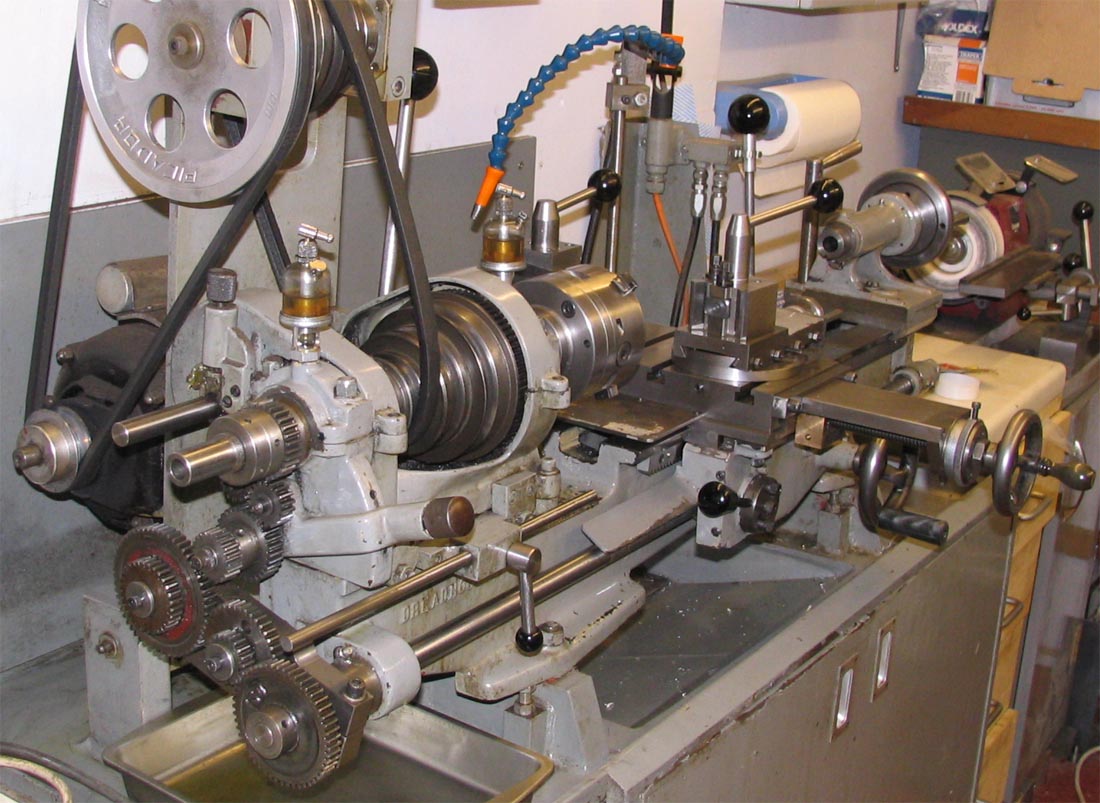

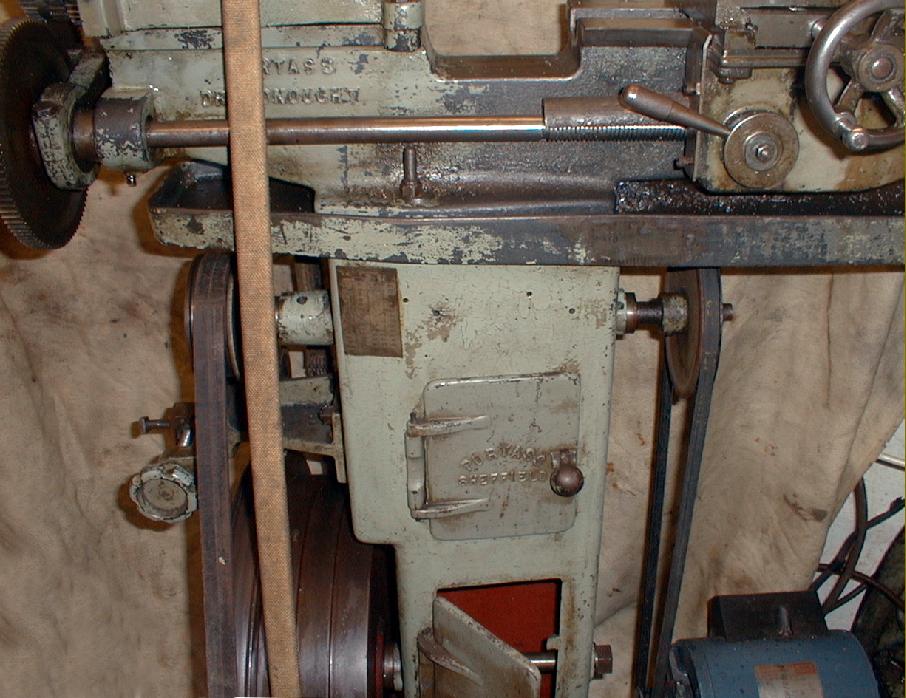

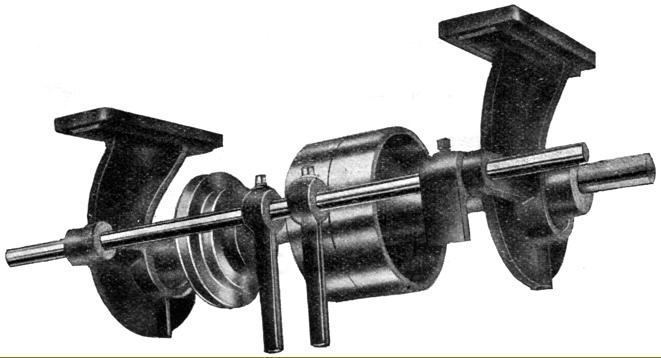

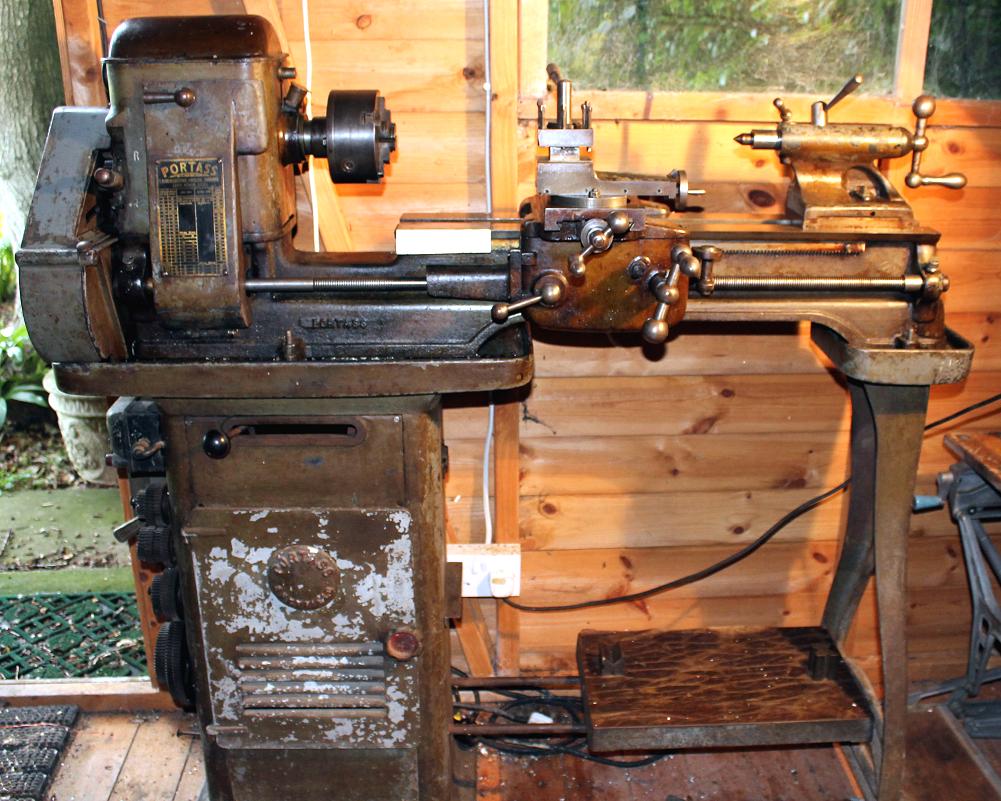

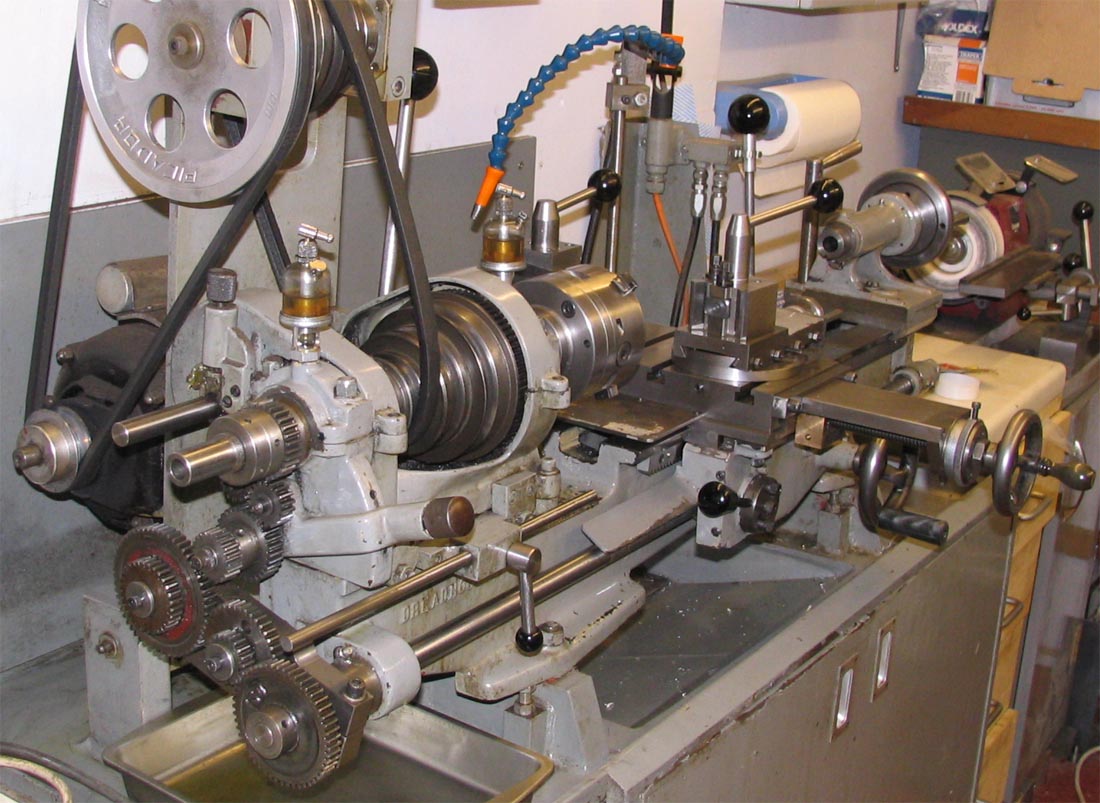

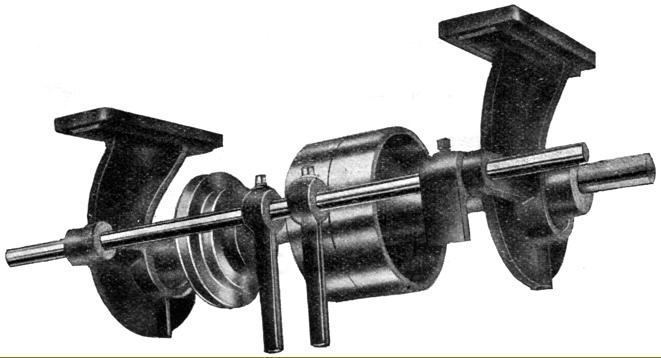

Virtually unknown this larger Portass lathe (we'll call it the "Big Dreadnought" was listed by the makers during 1951 as a 4" x 24" - but was actually slightly larger with a real centre height of 45/8". Priced at a considerable £144 : 7s : 6d (the 6d was important…) it was supplied on either a sheet-metal or massive cast-iron underdrive plinth (with a cast leg and chip tray) and fitted with screwcutting by changewheels using a 3/4" z 10 t.p.i. leadscrew. Mounted inside the stand, the motor was fitted with a long flat pulley and drove up to a simple countershaft fitted with a type of clutch known as "fast-and-loose" - which is, unfortunately, nothing to do with a women but an arrangement where two pulley are mounted side by side, on a common shaft, with one free to rotate and the other fixed. When the belt is on the loose pulley the drive remains unconnected but, when shifted across to the fixed (in this case by a lever protruding horizontally through the front face of the stand) the drive is engaged. The wide motor pulley was, of course, necessary to span the width of the two upper pulleys. Final drive to the headstock was also by flat belt running over a 3-step cone pulleys and passing over the front and back faces of the headstock - a bolt-on cover at the front giving access to the belt run. Bored through 5/8", the spindle ran in bronze bearings, had a No. 2 Morse taper nose and carried a 3-step pulley. To accommodate the belt run, the backgear assembly was mounted above the spindle line - hence the unusual height of the headstock - with a meaningless advertising puff in the sales literature describing it as being of the "top-geared" type. If the lathe was not fitted to the maker's stand a cover plate at the back of the headstock could be removed to allow drive by a rear-mounted remote countershaft. The unusual backgear assembly was not the only eccentricity - because the gap in the bed was too long (it allowed work 13-inches in diameter to be swung) the front spindle bearing and spindle nose were extended outwards to give the cutting tool a better chance of reaching up to the chuck jaws. With a faceplate fitted the problem was even more serious - and only fresh air supporting the front end of the saddle at the forward limit of its travel.

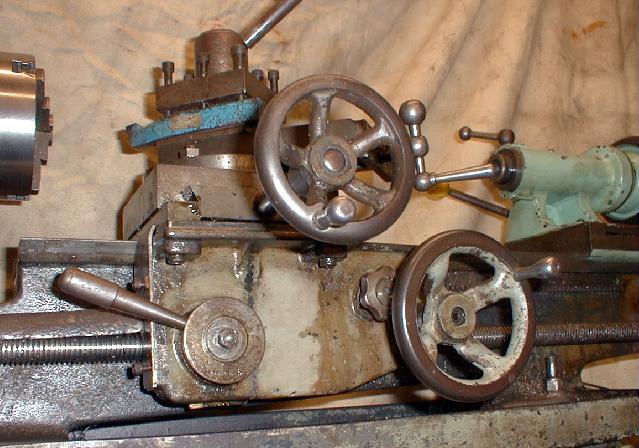

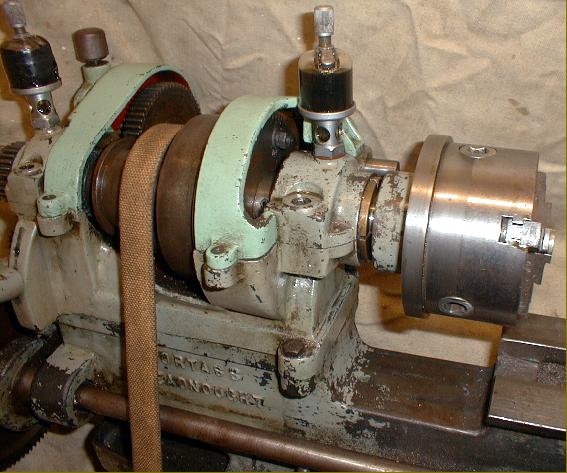

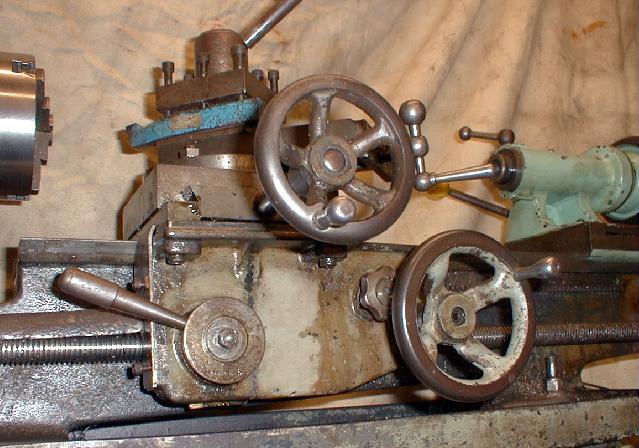

Robustly constructed, the carriage was fitted with a heavy apron holding bronze leadscrew clasp nuts and step-down gearing for the hand traverse. Of a decent width, the cross slide carried a top slide able to be rotated through 360° and equipped with a 4-way toolpost. Most unusually - for this was seldom seen on any Portass lathe - both slides had micrometer dials, neatly engraved on the flat rim of the handwheels. It is believed that a batch of these lathes, with their centre height increased to 51/8", was exported to Indonesia during 1963..

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

One of few survivors, a superbly original and low-hours' 45/8" Big Dreadnaught

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Carriage assembly of the "Big Dreadnaught"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The "Phallus" Dreadnought

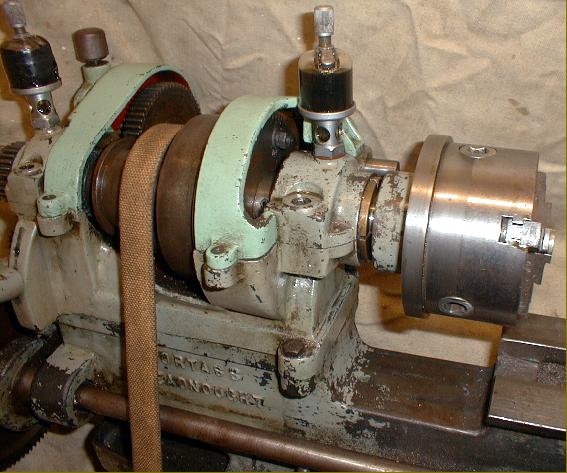

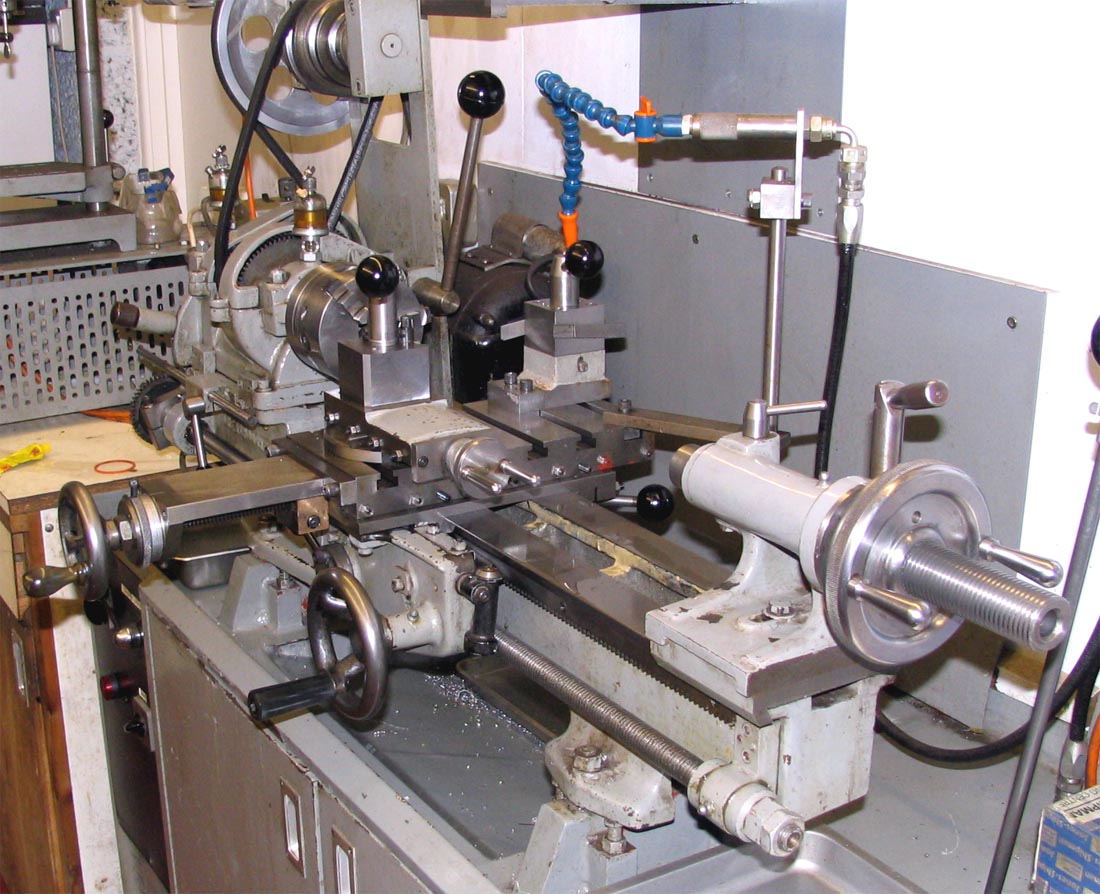

Bought new by the London Rubber Company (makers of "Durex" condoms) in February 1942, this Portass Dreadnought spent its early years turning moulds for (well, what do you think?) until it passed to a Russia firm - who complained that it just did not have the capacity they needed. Re-imported to England, it passed first to a Nottingham engineering company and then, in 1954, to its present owner, Neale Chaplin. On its purchase, evidence of a hard life came to light and Mr. Chaplin set about a comprehensive rebuild - this involving some careful modifications to overcome a number of the limitations inherent in the original design. Although modestly priced when new, the Dreadnought was an honestly-built, accurate machine and, while the cosmetic finish may have left something to be desired, the basis was there for an impecunious (but skilled owner) to develop a much-improved lathe. Notable on the machine featured here are a number of interesting modifications including a neatly-constructed hinged V-belt drive countershaft unit; drip-feed oilers for the spindle-bearing; a beautifully made T-slotted cross-slide (large enough to be used as a boring table - note the closely-spaced gib-strip adjustment screws and three locks); a hugely extended cross-slide end bracket and feed screw (this to give increased travel and so make better use of a vertical milling slide) and a large micrometer dial; quick-set and 4-way rear toolposts (the latter essential for easy parting off); an adjustable carriage stop, coolant equipment, a Myford thread-dial indicator and, the crowning glory, an expensive Burnerd "Grip-tru" precision 3-jaw chuck.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hardly a handsome machine, but solidly built and highly effective.

To the left and below is a Dreadnought Lathe built in January, 1943 and identical to that illustrated in the advertisement towards the top of the page. Fitted to the "Underdrive" pedestal stand, the only modification to this "Green List Dreadnought" has been a change from flat to a V-belt drive from the motor to the first countershaft pulley - a sensible modification.

In 1976, thirty-three years after it was made (and sixteen years after the model went out of production), Portass made the new owner a special T-slotted cross slide and vertical milling slide for it - this attention to personal service was a mark of the Portass company, where all enquiries received a detailed reply from Mr. Portass himself. More pictures here.

Although a simple and rather old-fashioned lathe Dreadnought was accurate and honestly made and some experienced owners took advantage of this by making a series of simple, well-engineered modifications that overcame many limitations of the original design and produced a much more versatile and easily-used machine..

A decent length and hence good "wrap-around" is essential for successful flat-belt operation and when I first saw the remarkably well-preserved lathe pictured below the owner had arranged the flywheel-drive belt so that, instead of passing under the jockey pulley and increasing the belt contact, he had passed it over the top - and so reduced it. It says much for the machine's capabilities that he had, nevertheless, managed to make two model locomotives before the error was pointed out to him.

Originally, the lathe was supplied with heavy cast-iron covers over the changewheels and front section of the large drive pulley but, unfortunately, these have been lost. The headstock-bearing drip-feed oilers were not originally fitted, but every small lathe benefits from their installation - they are completely reliable (if rather fragile) and you can see exactly how the oil supply is functioning.

A version of the much lighter "Model S" was also available fitted to a stand of this configuration - but, usually being on a tight budget, the typical "S" buyer can seldom have been tempted by such luxury and consequently these versions are particularly rare.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Substantial headstock bearings fitted with the those

old-fashioned looking but reliable drip-feed oilers.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

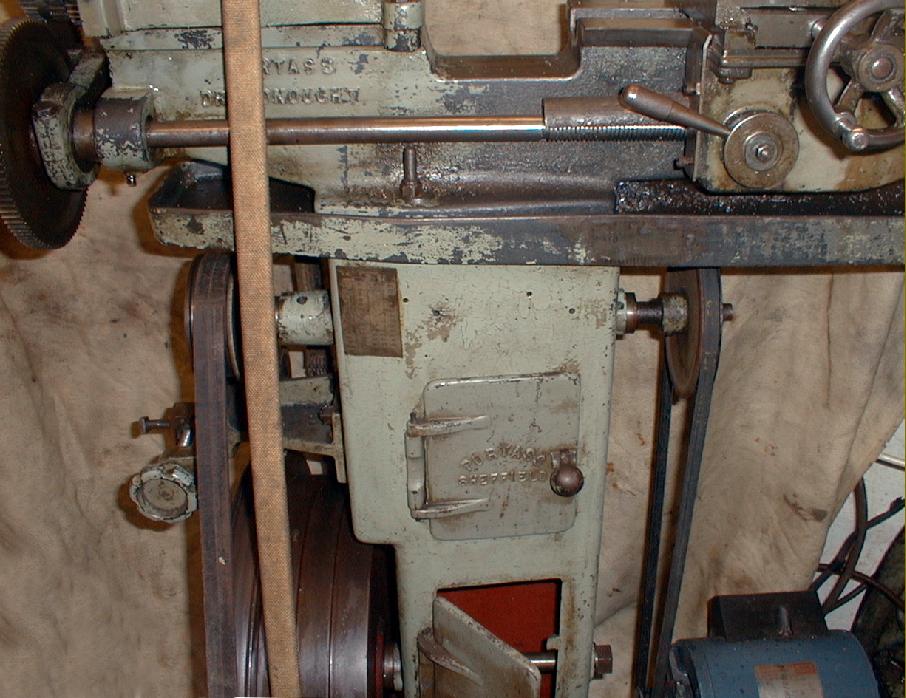

A proper tumble-reverse mechanism and a fine-feed set of gears for the leadscrew drive.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Substantial and properly-made cast-iron hand wheels

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Handwheel adjustment of the belt tension was provided by arranging for a jockey pulley to wrap the belt more tightly around the large drive pulley.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In its original form the flat belt drive from motor to countershaft would almost certainly have been a cause of trouble. The motor pulley was too small for effective grip and a change to a V belt set-up would have been a great improvement - as the first owner soon discovered.

As a point of interest, on many of the smaller American South Bend lathes the electric-motor shaft carried a V pulley, with a V belt driving onto large-diameter, narrow, flat pulley. This rather unusual arrangement (of a V belt on a flat pulley) worked very well even if, to modern eyes at least, it appears illogical.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Listed until the early 1950s (when even Mr. Portass admitted in his publicity literature that this was a "museum piece"), the Portass 4" x 23" "Wood and Metal Turning Lathe" could be had in various forms from a simple bench Type to one mounted on a self-contained treadle stand.

Running a ball race at the front and a gunmetal rear bearing (with thrust provision) the hollow spindle had a 7/8" x 12 t.p.i. Nose, a No. 1 |Morse taper socket. And carried a 3-step cone pulley to take a 1-inch wide flat belt. The flywheel was of generous weight and ran (unexpectedly for a Portass) on ball bearings. In 1938 the lathe was priced (as shown, with treadle motion) at £11 : 0s : 0d. Or for bench mounting at £7 : 0s : 0d. A metal-turning compound slide rest was £2 : 10s : 0d, backgear £1 : 17s : 6d and a separate countershaft £2 : 15s : 0d..

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

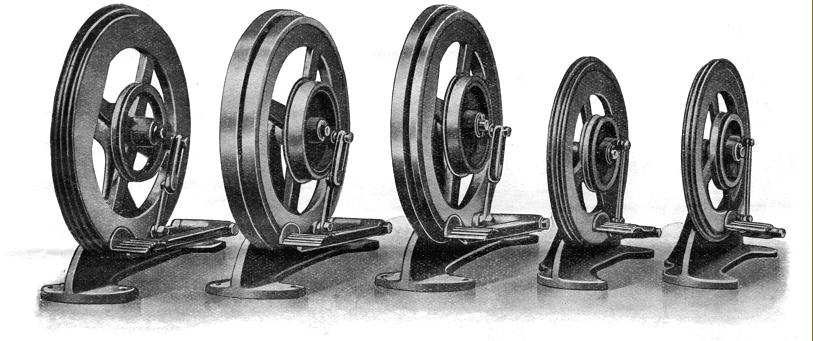

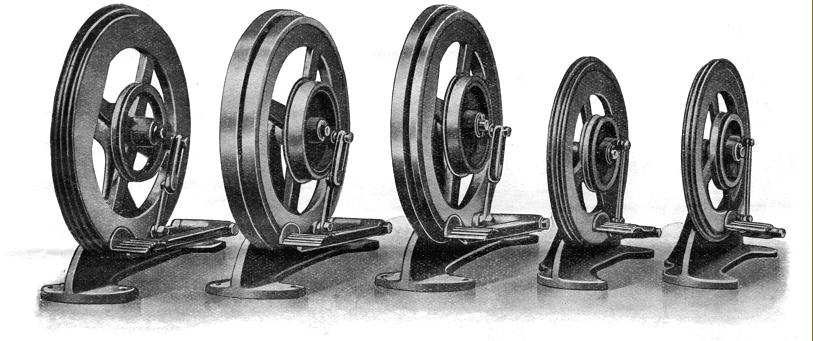

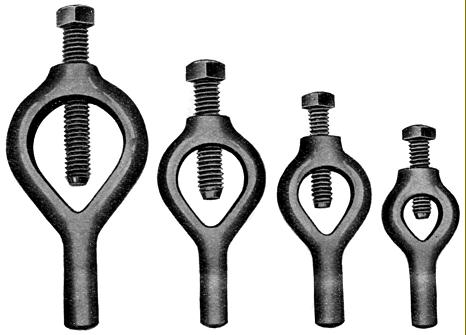

Portass "foot motors" - used to drive a lathe mounted on the owner's own bench

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

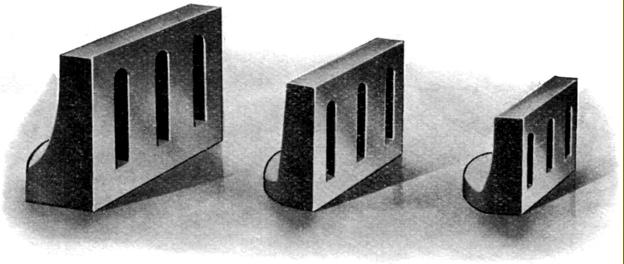

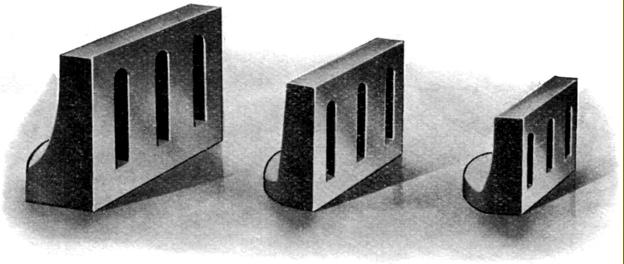

Having, in their earlier days, a foundry on site, Portass were able to manufacture their own cast-iron angle plates

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

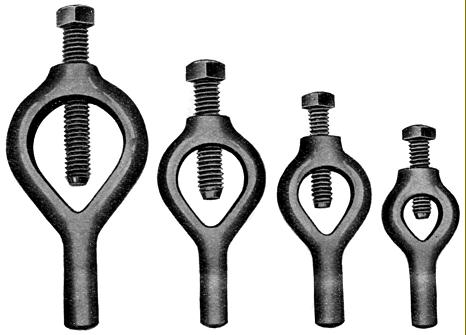

Crude 4-jaw independent "dog chuck"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

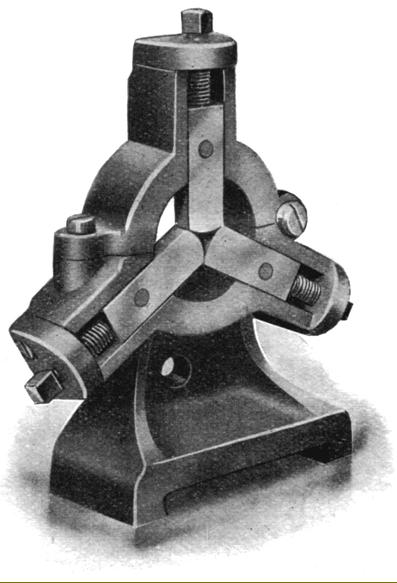

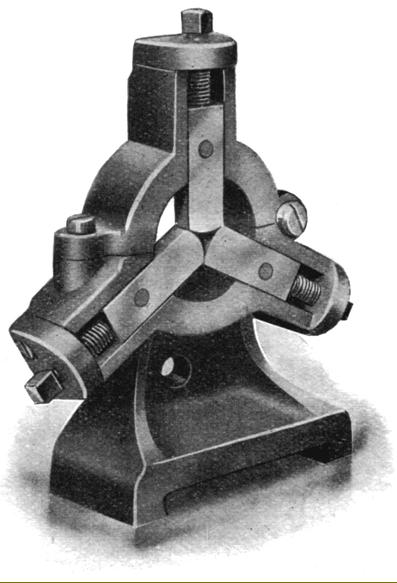

A typical Portass fixed steady

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

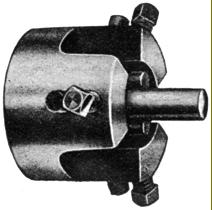

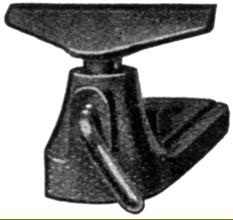

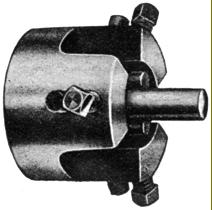

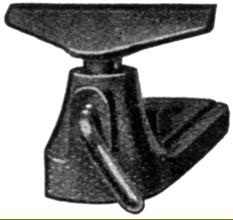

Portass fast-and-loose countershaft with belt striker

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

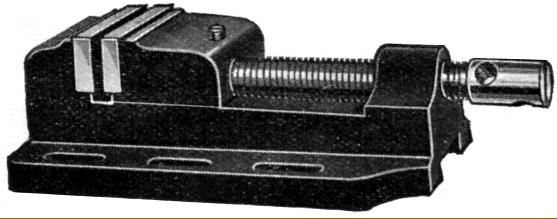

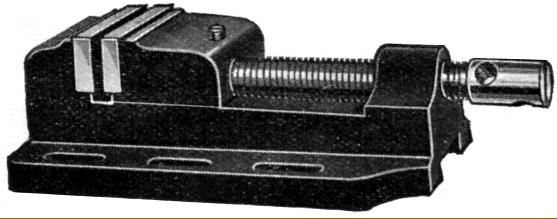

Portass vice with distinctive 6-slot base

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

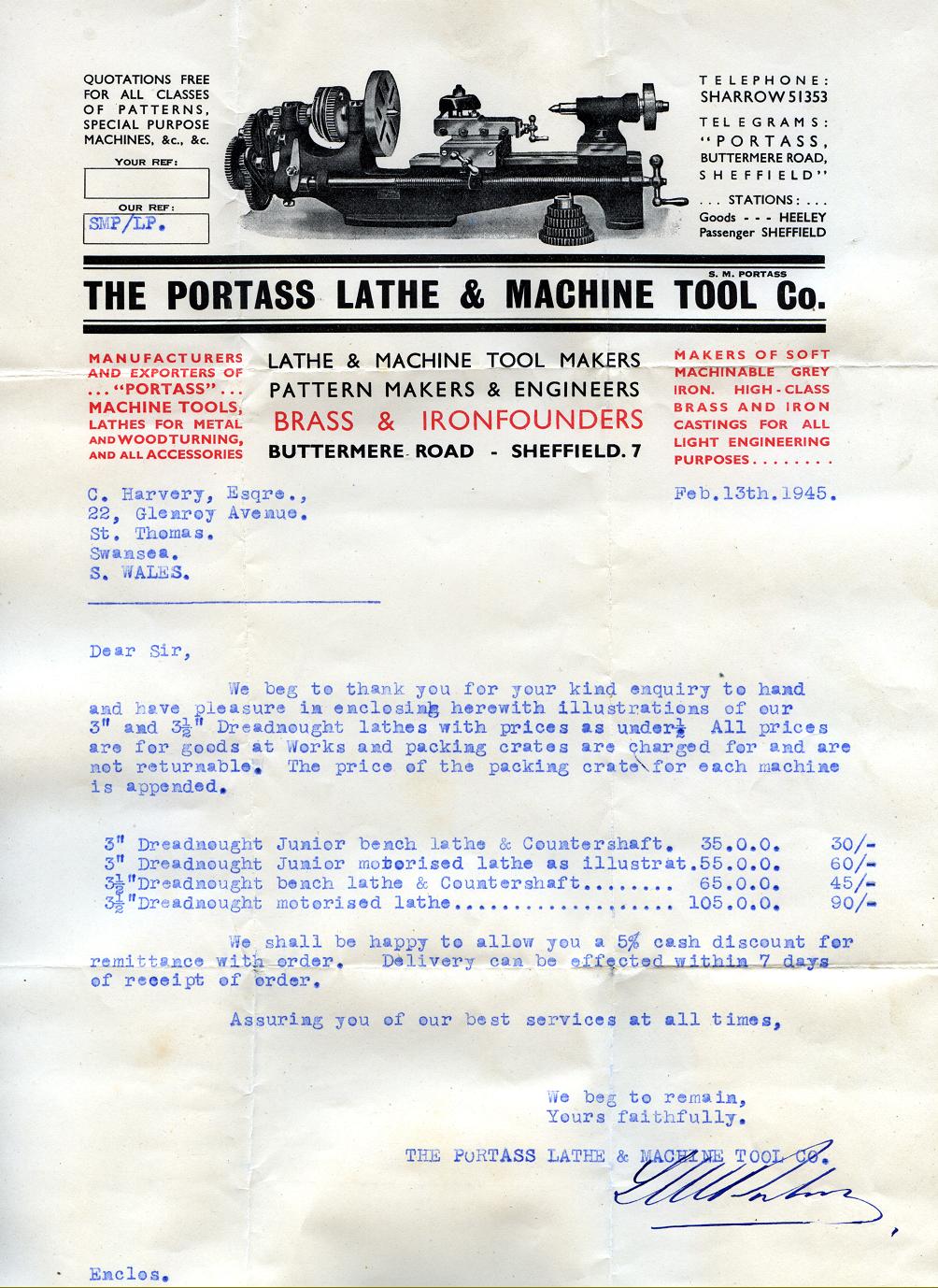

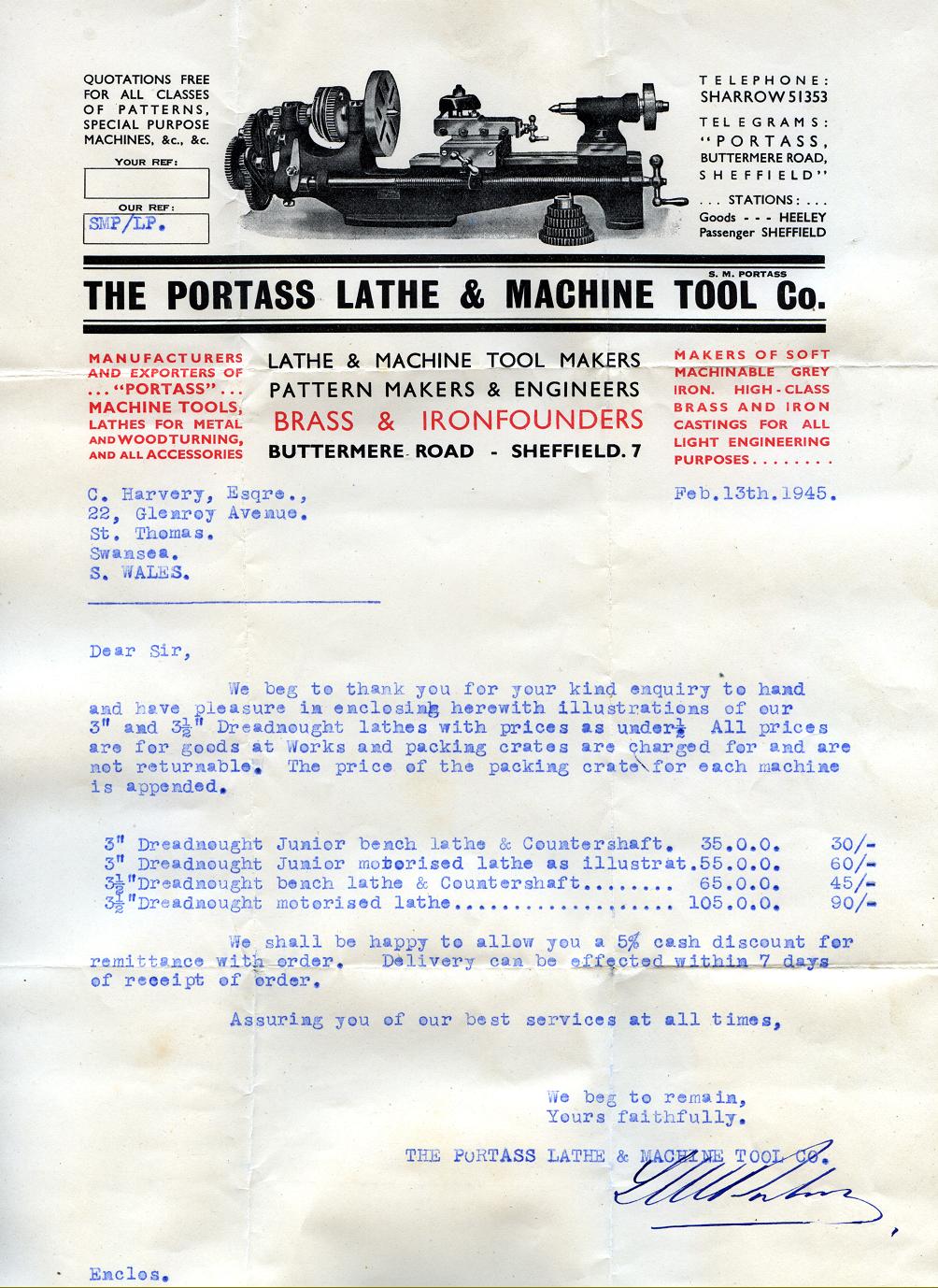

With World War 2 is still not over - and an enquiry arrives for the supply of a small lathe

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|