|

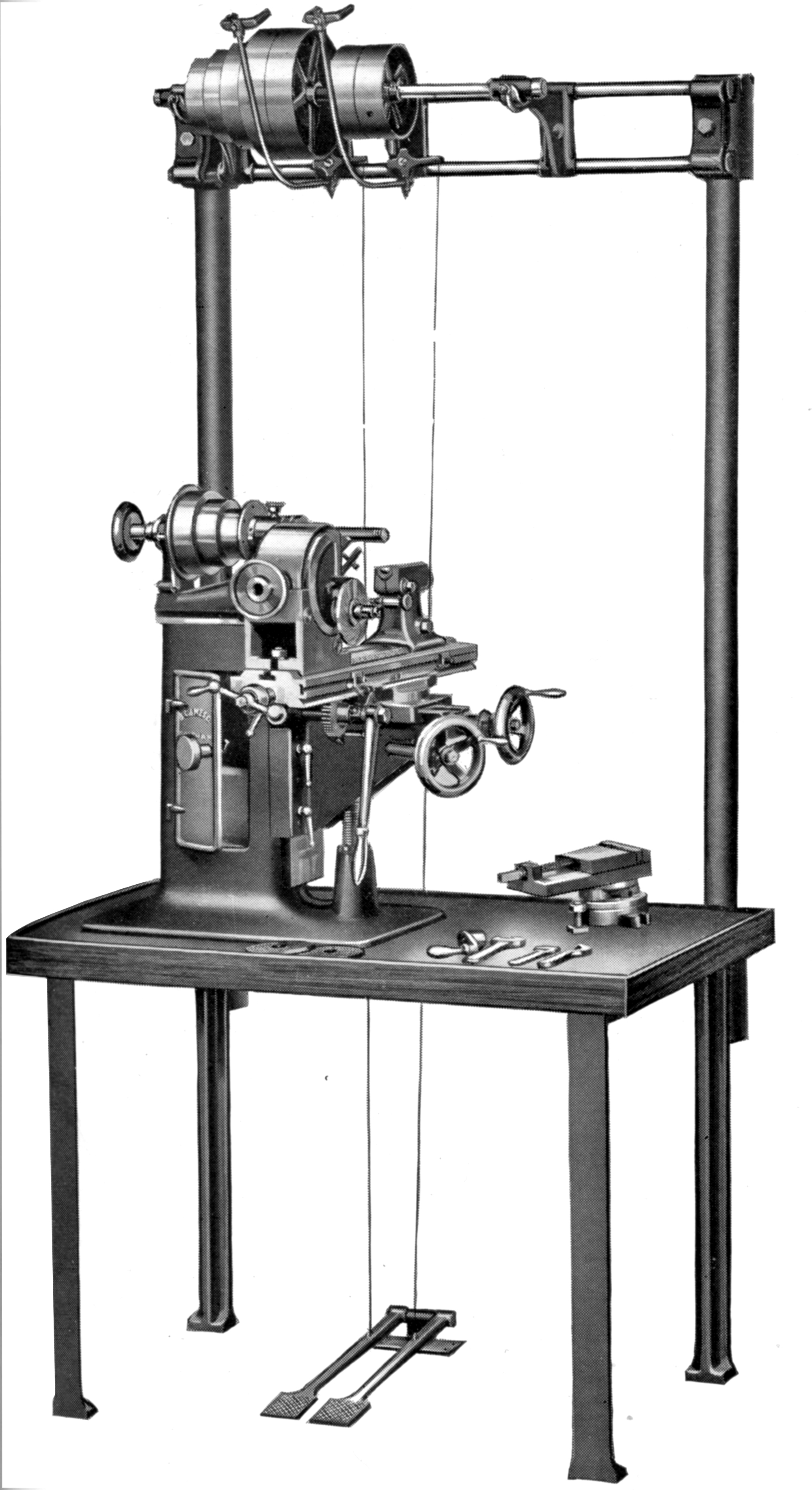

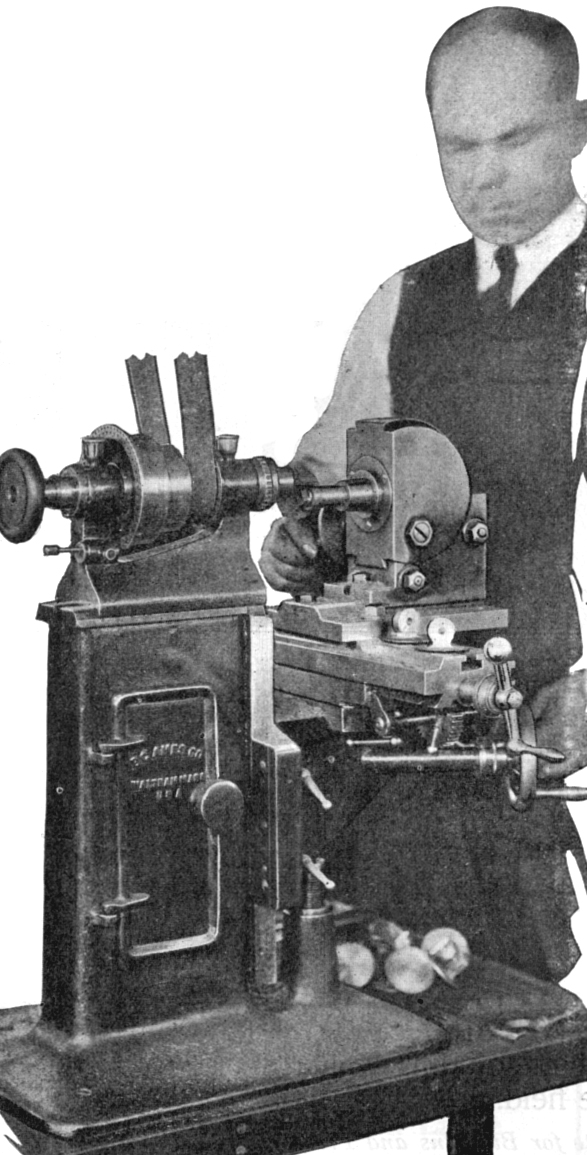

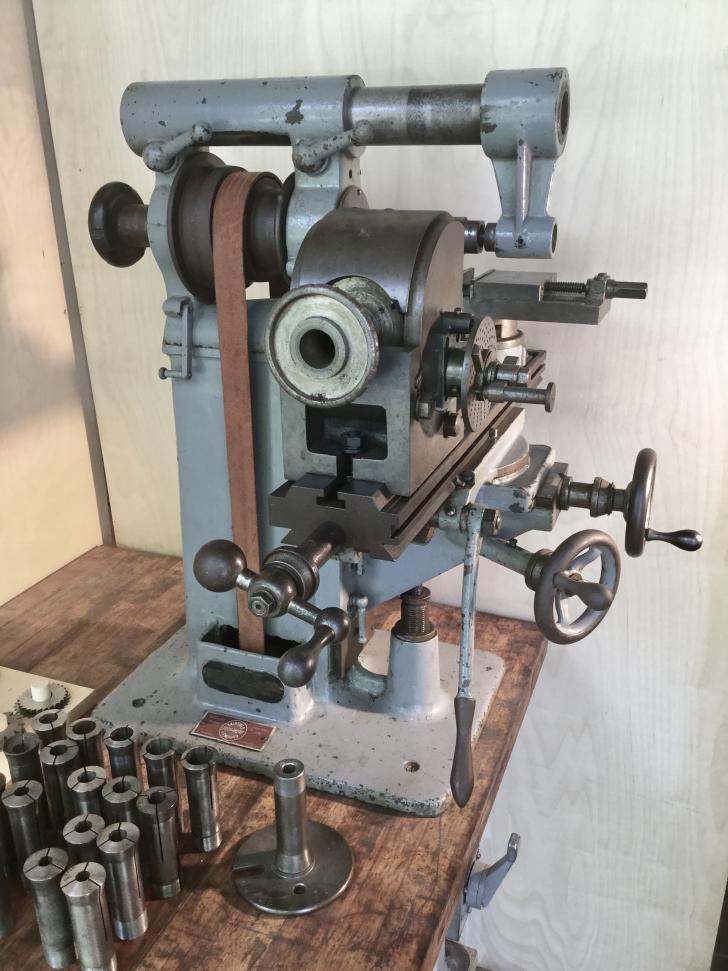

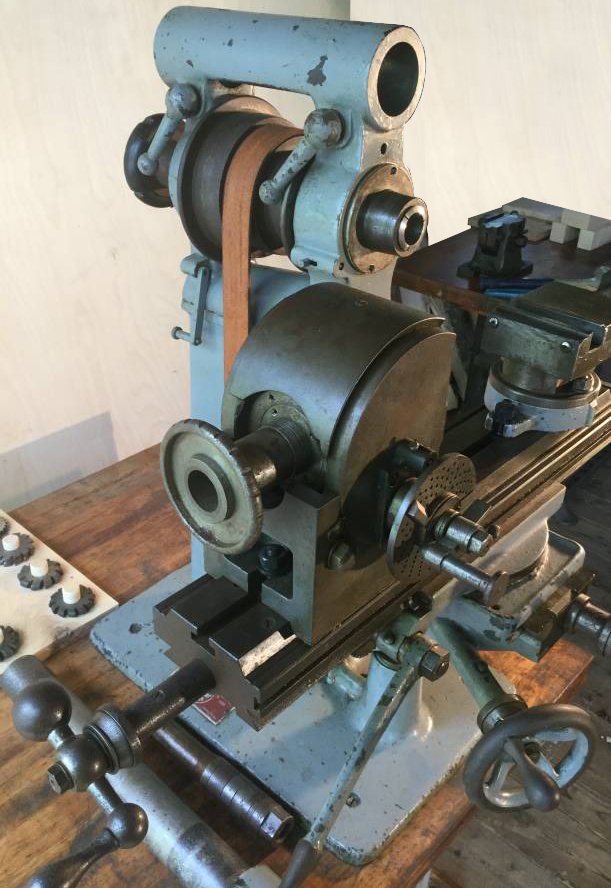

From the early years of the 20th century, until at least the early 1930s, many makers of precision machine tools including Pratt & Whitney, The Waltham Machine Works, Rivett, Cataract and Ames offered a small bench milling machine based around the headstock from one of their precision bench lathes. Ames claimed that theirs was for: "small, light milling on tool, jig and model work as well as on regular manufacturing." It was described as: "..built solid and compact, with a large range of working space, and will handle medium work within its capacity, yet is handy in its operation for the finest and most exacting of work".

With a collet capacity of either 5/8" or 1" (and spindle bores of 3/4" and 11/8" respectively), Ames selected the headstock from the No. 3 lathe for the conversion, although those customers requiring a more rugged assembly could choose a specially made unit that incorporated an overarm and drop bracket able to support a traditional, full-length cutter arbor.

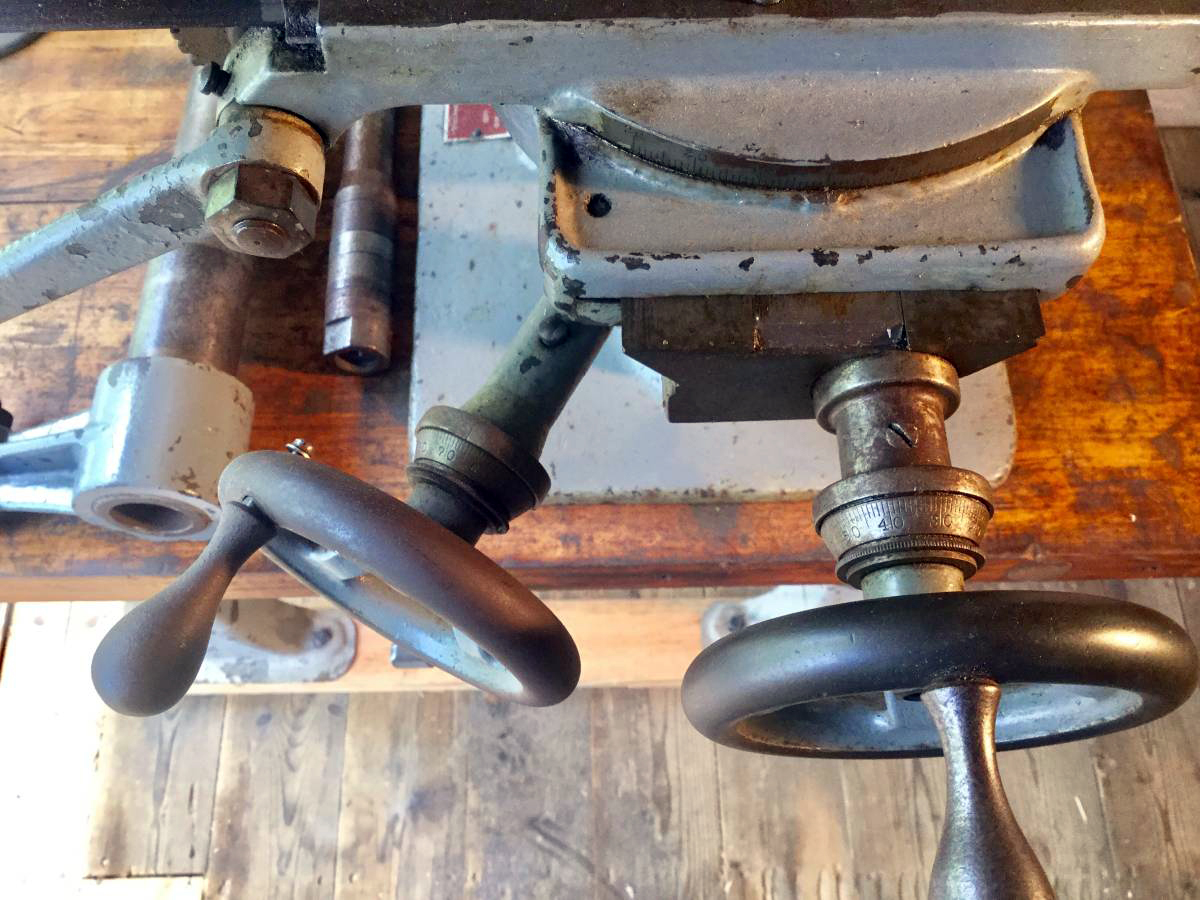

Although very early machines may have had a table with a (working) surface just 12" long, most seem to have been fitted with one some 9" longer, 4" wide and with a working surface 19" by 21/2" or 3". The table was arranged to swivel 45° either side of its central position and, to allow the greatest possible versatility in mounting ancillary equipment such as high-speed grinding and cutting heads, slide rests and tailstocks, its top surface took the exact form of an Ames lathe bed. The 40° V slides of the table were hand scraped to a perfect fit and provided with a gib strip adjustment for wear. The longitudinal travel of 12" could be operated by both a screw and a quick-action rack-and-pinion feed (against adjustable stops) whilst the cross travel of 3" and the vertical of 71/2" were both by screw feed only. All three feeds used screws with milled, Acme-form threads that ran through long bronze nuts; the micrometer dials were of the zeroing, friction-type and the knee's elevating screw was fitted with ball-bearing thrusts that operated within hardened-steel retainers.

An important part of the miller's equipment was the worm-and-wheel driven tilting dividing head that could swing 83/8" over the bed, set at any angle from 10° below the horizontal to 5° beyond the perpendicular and, when fitted with the optional tailstock, accept up to 101/2" between centres. The spindle, made from carbonized, hardened and ground steel accepted the same 5/8" or 1" collets as the headstock while the three supplied dividing plates gave a range of divisions between 2 and 312. The whole unit was most beautifully made and, instead of rotating on just a small centre bearing, the swivelling part if the mechanism slid on its periphery inside a very heavy, closely fitting shoe.

Of the same very high quality as the other accessories, the heavily built swivel base vise had 31/4"-wide jaws that opened to a maximum width of 21/4".

Although a small horizontal miller can be a very useful tool, especially when equipped with a range of accessories, a vertical machine is so much more versatile and, in an attempt to expand their miller's appeal, Ames offered a vertical head that slid on in place of the horizontal headstock; unfortunately, the capability of the head was compromised by the absence of a quill feed and (apart from those generated by the countershaft) only one speed.

Although advertised for bench mounting the makers also offered an oak cabinet, similar to that supplied for their lathes, and both cast-iron and open-frame metal stands; the stands are shown at the bottom of this page.

While in 1926 a No. 3 lathe complete with a compound slide rest cost $235, the miller was, at $348, considerably more expensive and, as it came without a headstock, should the owner have been unfortunate enough not to own an Ames lathe from which to borrow one, an additional $84 for the 5/8" capacity unit or $114 for the 1" version. If the stronger overarm type was specified, those cost $120 and $150 respectively for smaller and larger sizes; the machine vice an additional $60, the dividing attachment $160 (5/8" collet) or $190 (1" collet) with an extra $45 charged for the mounting shoe - which leads one to suspect (although not mentioned in the sales literature) that the rotating element might have been employable on its own. Thus, a complete miller ready to work, save for a countershaft or drive gearbox, cost over $800 at a time when the pay of an average workman was just $10 a week.

Besides the machines illustrated on this page Ames also listed the Triplex Multi-Function Machine a rather wonderful and very compact combination lathe, miller and drill press with a built-on motor unit..

|

|