|

Based in Wildbad (formerly Calmbach) in Germany's beautiful Black Forest, the Gauthier Company is still in business today as Prontor GmbH producing assemblies and subsystems for precision machines and items concerned with medical technology.

Founded in 1902 by Alfred Gauthier in Calmbach in the Enz Valley, in 1902, the company became famous for making camera shutters, their first product, in 1904, was the Koilos three-leaf type with a leather brake. Eventually, shutters branded as Ibsor, Vario, Pronto and Prontor were all made - the writer is pleased to find that the company made the special rotary disc shutter in his "Robot" camera.

Making camera shutters is akin to making watches and hence requires a variety of both high-precision machine tools and skilled craftsmen and women. Inevitable, Gauthier found that the ones on offer failed to meet their particular requirement - and, in 1909, started to manufacture their own - including automatic Swiss-type lathes and miniature gear hobbers. A similar situation had also arisen at Deckel, then a company also known for its camera shutters using the brand name "Compur", a type widely used by leading manufacturers including Hasselblad inside their "Type C" lenses.. Deckel's interest in developing its own machine tools resulted, first, in the FP1 universal miller and then a series of other high-precision types. As was not unusual in these situations, Gauthier and Zeiss had the foresight to take a share in Deckel in 1910.

During WW2 fuses for hand grenades were the main item produced, the Company afterwards being requisitioned by the occupying French military government. By 1949 production had resumed of shutters and machine tools; high-class optical production machinery followed in 1964 and in 1969 items of medical technology. In 1976 the West-German Zeiss group handed over the whole production of shutters of the was handed over given to Gauthier. In 1999 an increasing demand arose for optical devices to make computer chips, a market that Gauter, with its highly-developed skills base, was able to fulfil.

If you've ever wondered how the thousands of millions of screws, other fasteners and assorted highly-accurate cylindrical parts are made so cheaply, the answer lies in lathes known as "Swiss-Autos" and single and multi-spindle automatic lathes.

The Swiss-Auto was originally an entirely mechanically-operated lathe that, alongside its close cousin the single-spindle automatic, was a machine tool designed specifically for the economical mass production of such parts. Until the advent of electronic circuits, a far greater range of manufactured items required such fittings, from use in watches, clocks, cameras and other optical devices to such items as parts for typewriters, mechanical calculators and a vast range of cars, aircraft and marine and scientific instruments. The originators of this specialised lathe were based in Switzerland, in the large village of Moutier where, from the early years of the 20th century, three competing Companies, Tornos, Bechler and Petermann existed side-by-side. However, beginning in the late 1960s, a series of takeovers and mergers resulted in one surviving Company, Tornos S.A. having absorbed the others. The men responsible for pioneering developments in the field were Joseph Petermann, André Bechler and, the owner of Tornos, Willy Megel - their lathes all incorporated three essential design features: a headstock (or headstock spindle) able to slide backwards and forwards; a series of precisely-adjustable toolholders arranged above or around the spindle nose in a fan shape and operation of the various feed and other movements by specially formed cams.

Even today, during the early decades of the 21st century, such basic, mechanically operated lathes still find employment where a simple, low-cost yet high-precision solution to manufacturing needs is required (the writer receiving numerous enquiries from countries such as India). Though complex mechanisms in their own right, the Swiss-Auto's ease of operation and running adjustments, compact dimensions and reliability over very long production runs are still hard to beat - though making the cams and setting up the numerous adjustments does take some mathematical knowledge, skill and experience.

The writer has personal experience with such a machine that, decades old when installed in a friend's sound-proofed domestic garage and fitted with an automatic bar feed unit, could be left running non-stop for days and nights filling hoppers with profitable little items.

Now adapted to computer control, both the Swiss Auto and single-spindle automatic are unsurprisingly, still being built by numerous makers worldwide (Japan having had considerable success in the field) - a term often used for this trade is the "Bar-turning Industry".

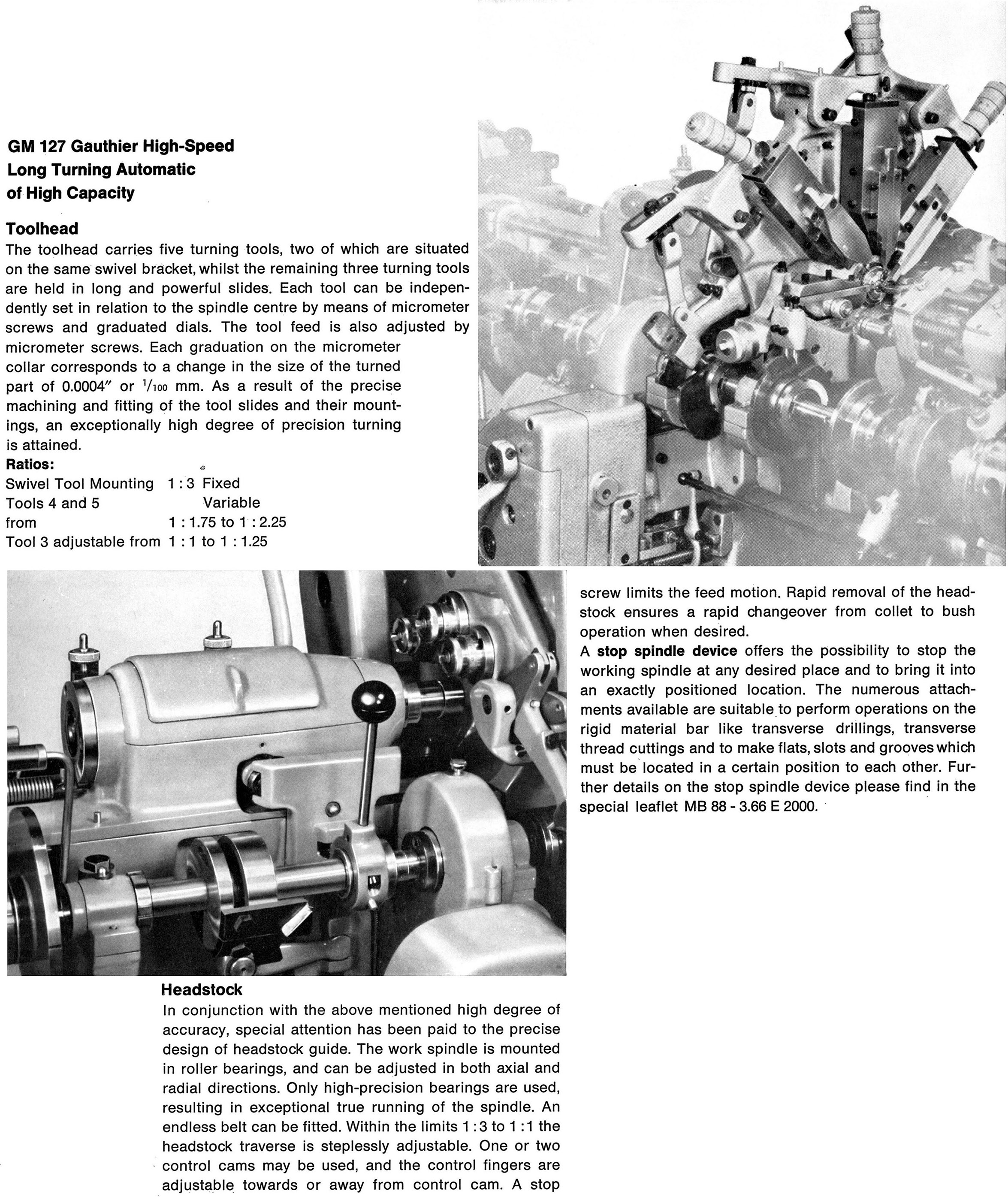

All original, mechanical-type Swiss-Autos were arranged along similar lines with, depending upon the model, up to six independent tool holders arranged radially on a cutter frame fixed in front of the (right-hand positioned) headstock nose. Each tool-holder was arranged to slide, its action triggered by a rocker arm connected (via a series of linkages) to a rotating cam. For round components only finely ground bar stock could be used, the job being either very short and so requiring no outboard support, or long enough to pass through one of several kinds of bushed steady that held the work both accurately and securely against deflection. The longitudinal feed was obtained by sliding the whole headstock along the bed, at various rates and timings, also under cam control. By combining headstock and tool movements, cam shapes, cam timing and with various types of cutting and forming tools (and by mounting accessories) the lathes could perform miracles of miniature production engineering. When producing tiny parts, an important point was the very precise adjustment of the cutting-tool holders - and in this the "setter" was, originally, the highly-paid king of the shop floor. In the early days the best results could only be obtained by long experience and trial-and-error-methods but, with the introduction of Petermann's "micro-differential" apparatus, where a micrometer was mounted on the end of each toolholder, the task became greatly simplified. The first setting took accuracy to within 0.01 mm of turned diameter and the second to within 0.001 mm (0.00004"). As one setter of these machines remarked: ….there is a sense of achievement and excitement when all the tools and cams are fitted and the machine timed up; and then, after a short session of adjustment, to go on and manufacture thousands of identical parts, all new and shiny..

|

|