|

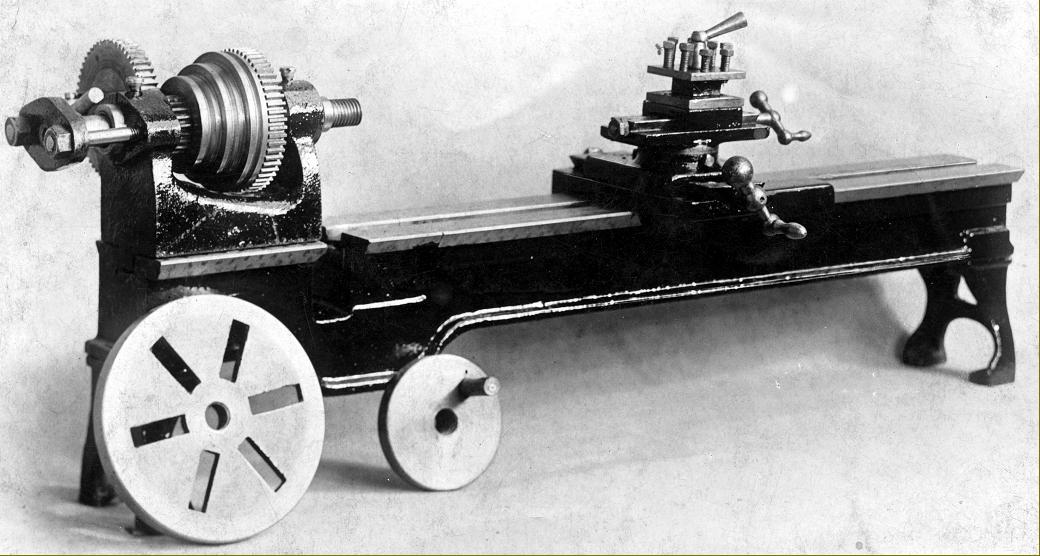

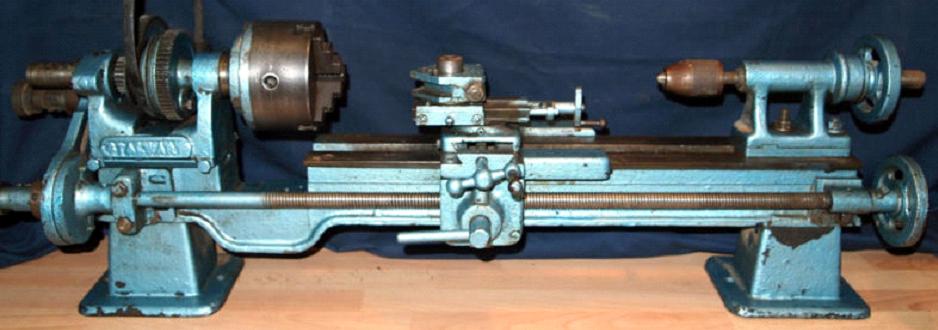

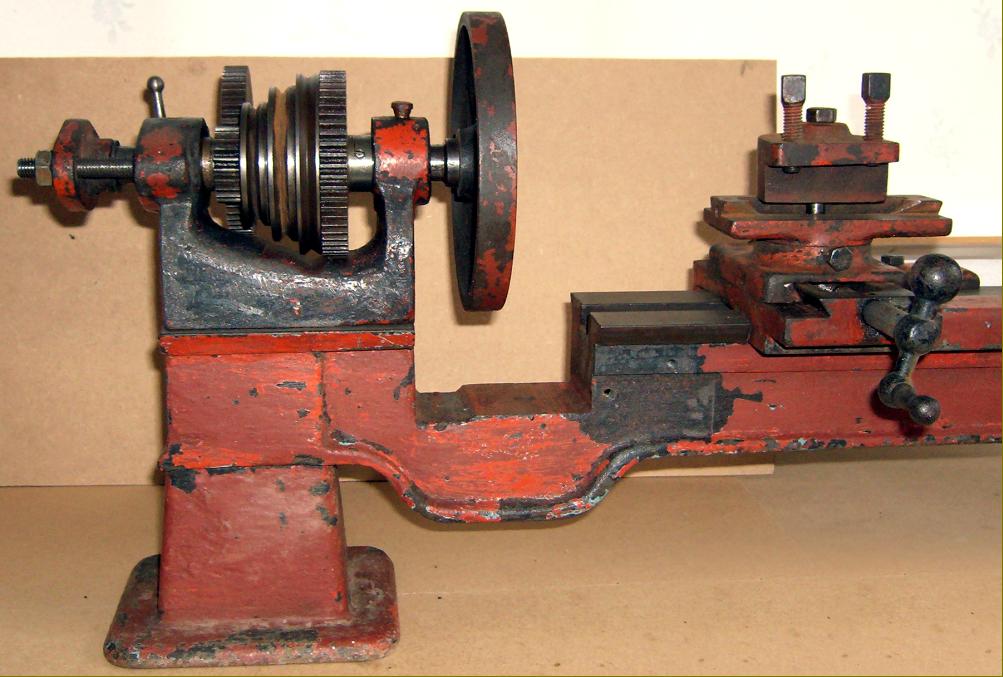

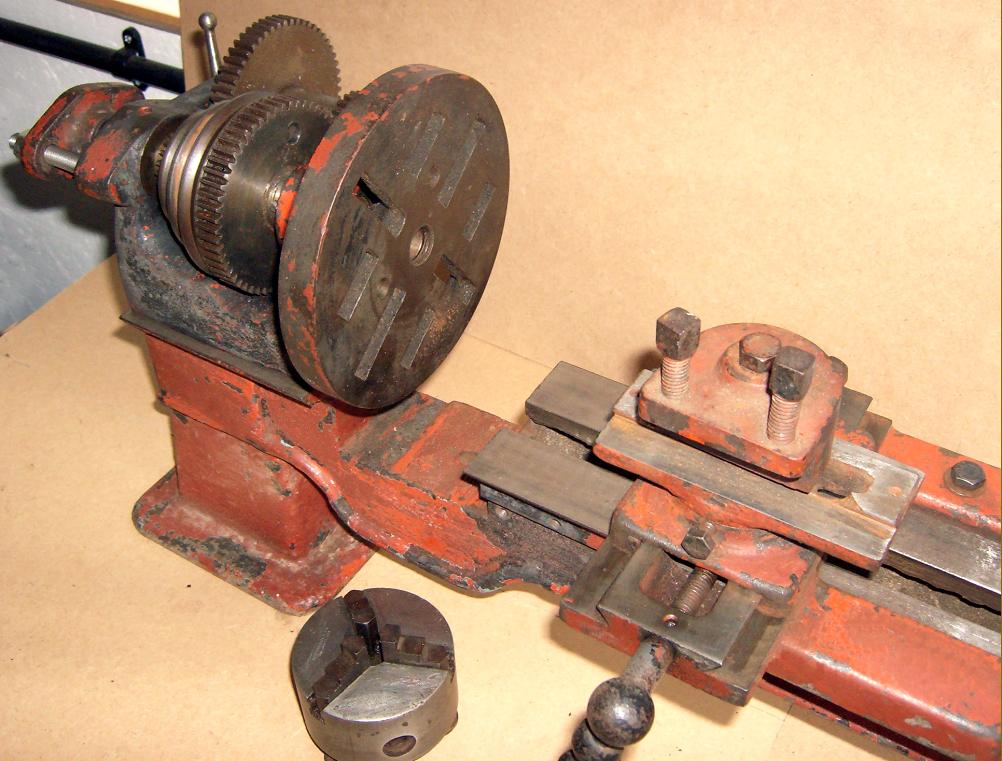

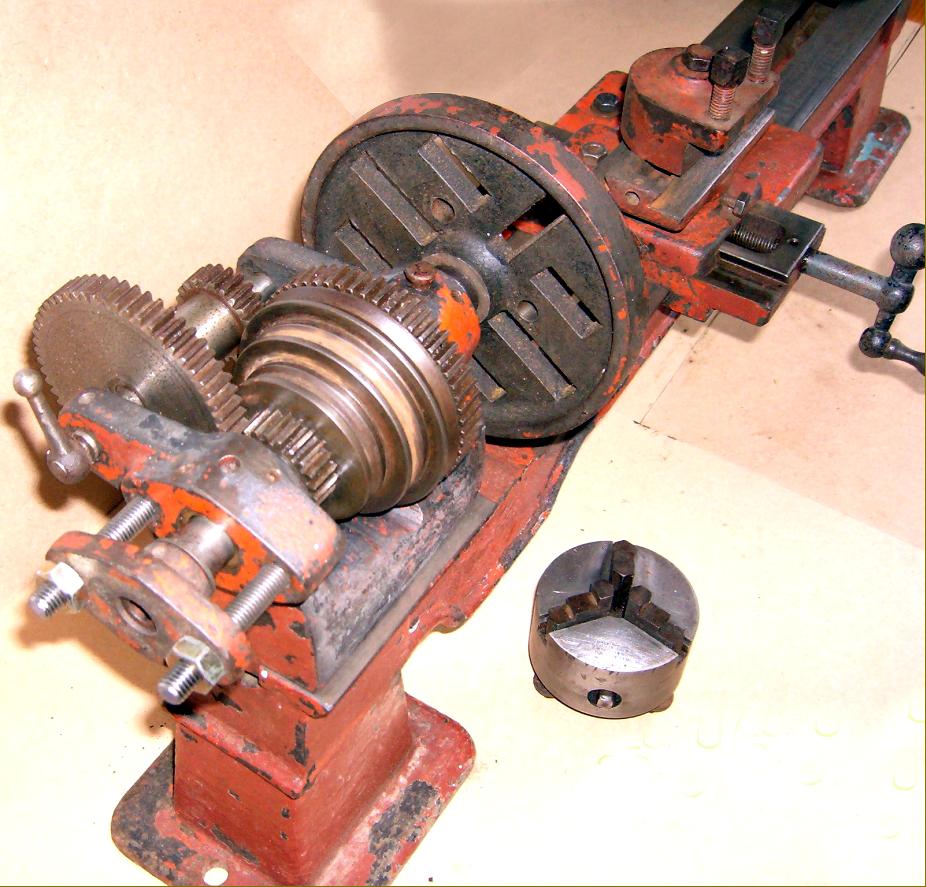

Typical of the small lathe intended for amateur use made during the first two decades of the 20th century, the 3" x 18" Stalwart was manufactured by Cryer and Dawson of Bingley, England. It was made in several form, from a simple plain-turning model with just a 3.5-inch travel top slide to provide a longitudinal feed, a version with a full-length Acme feedscrew to drive the carriage by a handwheel at the tailstock end and a fully backgeared and screwcutting types. However, judging from the very limited information available the full-width 2.5 : 1 ratio machine-cut backgear assembly was probably fitted as standard to all versions- and engaged by rotating its eccentric mount.

Of traditional English form, the flat-topped bed had a 60° front V-edge and a vertical surface at the rear. A removable gap piece appears to have been standard and, with it out, work up to 9.5 inches in diameter could be turned. Even with the gap out, the position of the cross slide to the extreme left-hand edge of the long saddle ensured that the cutting tool could (just) reach the spindle nose.

Fitted with a No. 1 Morse taper nose and bored through to clear 3/8", the chrome nickel steel spindle ran in adjustable bronze bearings, both being 1-inch diameter and 1.125" long. For a lathe of its time the headstock spindle thrust arrangement was of the decidedly old-fashioned type, as more commonly found pre-1900, with an outboard support carried on two posts screwed into the outside face of the headstock.

Drive was by the usual round leather 3/8" rope (a "gut" drive in contemporary parlance) running round a 3-step (2.5", 3" and 3.5") headstock pulley whose grooves were noticeably shallow

Although even cheaper lathes of the time were usually fitted with proper square-section top and cross slide screws, the Stalwart made do with ordinary Whitworth threads and, as a further economy, these ran in holes tapped directly into the metal of the slides so making replacement for wear difficult. There were no micrometer dials on the compound slide (a common omission at the time) and the screws were also right-handed, giving a "cack-handed" action where turning the screw to the right moved the slide backwards instead of forwards - fine if the operator used just the one machine, but potentially disastrous if other conventionally-arranged lathes were in the same workshop.

Although the lathe was generally well built (it weighed around 100 lbs) the top slide (fitted as standard with a 4-way toolpost) had a serious weakness, the ways were machined to leave only 1/8" thickness on the inside edge of the V and, on one of the lathes shown below, this has caused a section of the casting to break away. In addition, on the red-painted example, the feed screw was not parallel to the ways, being some 3/32" misaligned from end to end with the oil drillings similarly out of line.

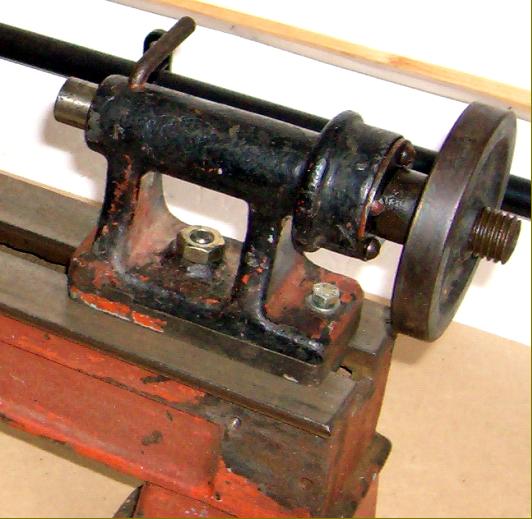

Able to be set-over for the turning of a shallow taper, the tailstock held a 3/4" diameter barrel bored through to clear 3/8" and with a travel of 3 inches.

The maker's offered a number of extras including (in addition to those already mentioned) a bench countershaft unit, a foot-motor with treadle motion to mount under the owner's bench, 1-inch raising blocks to increase the centre height, a T-slotted boring table, 9-inch radially slotted faceplate, a set of six turning tools mounted in a wooden block, an angle plate, hand T-rest, 3 and 4-jaw chucks and a simple bell chuck with four holding screws

Although it was thought until recent times that no examples of the Stalwart had survived, one in poor but salvageable order was found in 2005 and another, backgeared and screwcutting, in 2012.. If you have a Stalwart lathe, or other Cryer & Dawson machine tool or Company literature the writer would be delighted to hear from you..

|

|