|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Often greatly underrated, even by experienced engineers, the shaper was largely displaced from the amateur's workshop for many years by a flood of cheap, far-eastern vertical milling machines. However, being a surprisingly versatile and cheap-to-operate machine-tool it is now, in the early 21st century, staging something of a comeback. The many knowledgeable enthusiasts who baulk at spending large sums of money on easily-damaged end-mills and slotting drills necessary for use with a vertical miller know that many of the same effects can be obtained with a shaper, a few pence worth of ordinary cutting tools and a double-ended grinder to keep them sharp - there being no need for an expensive, difficult-to-operate tool & cutter grinder. As a bonus, as the machine is working, there is something inherently entertaining and satisfying in its regular mechanical motion - and an almost Victorian atmosphere surrounding the way in which it does its job.

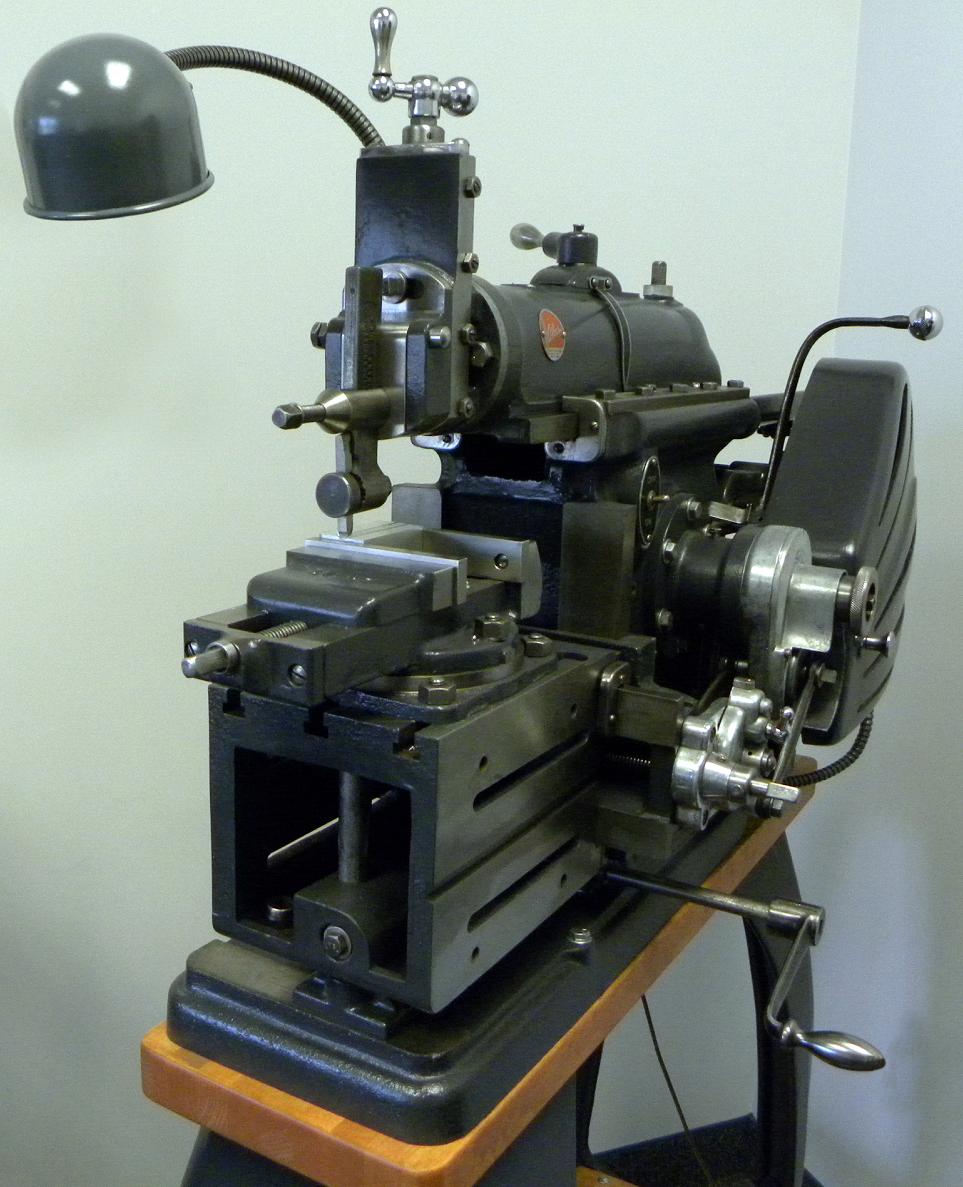

An important American contribution to the field of shapers intended for amateur use was the neat 7-inch model by Atlas. Introduced during 1938, it was also badged, like many other Atlas products, as the "Craftsman" for distribution in the USA by the mail-order company Sears and sold as the "Acorn" in the UK and the Austolite when manufactured (or marketed by Fred Price Engineering) in Australia.

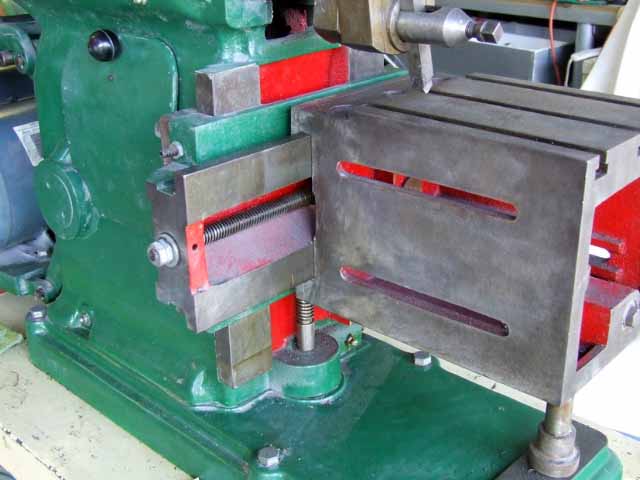

With just under 5" of height adjustment, the table had an automatic cross feed worked in both directions (at the flick of a pawl lever) and fed the cutter at between 0.005" and 0.025" per stroke of the ram - with a total sideways travel of 9.375". On early models the housing for the table ratchet feed was in cast-iron, with the first having a plunger to operate reverse and the later type a lever. Expensive to produce, this item was quickly replaced by one in ZAMAK, a choice of material that would prove to be a considerable test of its strength and reliability. The 6-inch wide and deep box-form table was provided with three T slots in the top surface, two slots in each of the ground-finish side faces and was supported by an adjustable 3/4" diameter rod which travelled with the table as it moved - so bracing the front of the work table and eliminating, to large extent, the flex caused by taking heavy cuts. Unfortunately, the first production machines were without any form of table support - a significant omission which strongly suggests that prototype testing might well have been less than thorough.

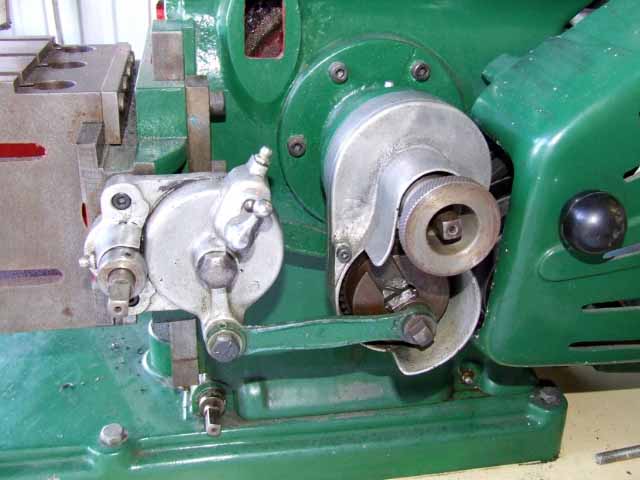

Neatly mounted on the rear of the machine, the self-contained V-belt motor-drive system carried a 1725 rpm single or three-phase 0.5 hp motor that provided four stroke rates of 45, 78, 122 and 186 per minute. The drive to the ram was though properly-engineered, well-supported gearing with the larger wheel 1" wide, of 10 d.p. and made from a semi-steel iron. The slotted crank arm was in nickel-chrome-vanadium with a ground finish on its outer surfaces and ground and lapped on the inner "slide" ways. The upper crank pin ran on an Oilite bush with the stroke-positioning screw, crank pin and slide lubricated through a wick oiler contained within the ram clamp screw handle. Lubrication for the slide must have been found inadequate for later models had an oil hole drilled through the centre of the "slide cover plate". The large "bull" gear was supported by a roller bearing on its near side to absorb the considerable radial loads placed on it and, at the end of its shaft to take thrust loadings, a deep-groove ball race. The drive spindle was hardened and ground, ran in roller bearings and carried pulleys which were dynamically balanced. The belt-tensioning lever doubled in duty as a clutch-come-brake and, acting on a brake shoe within an extra drum attached to the drive spindle, it meant that the machine could be stopped quickly - and without having to switch off the motor.

A rather good, heavily built swivelling -base 4" machine vice with steel jaws was fitted as standard: like all good shaper vises it was shallow (only 3" tall) but long enough (at 12") to hold a substantial lump of material. One crank handle was supplied with the shaper and, magically, it fitted all the controls: the vice, table elevation (with a supplied extension piece), hand cross feed, feed and stroke-length adjustments - and the stroke positioning.

Of particular interest to the amateur machinist was the fact that this machine, with its built in mounting tray, was one of the very few heavy-duty shapers capable of being bench mounted, requiring a space of just 18" x 32.5". Owners report that the Atlas shaper is capable of holding its accuracy over a long and strenuous life. In the year of its introduction it weighed, complete with the maker's vise, 240 lbs and was priced at $198 - though with a motor and guards the cost rose to around $260 and the weight to just over 310 lbs...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The first versions of the Atlas Shaper did not have a supporting bar under the front of the table ...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A later version with longer mounting foot and a support under the front of the box. On this model the table was fitted with swarf-excluding wipers. Note, in comparison with the earlier models, the larger cut-out in the door's bottom left-hand corner

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A beautifully art-worked picture showing details of the adjustable feed-stroke mechanism to the table (reversing) drive ratchet. The micrometer dial on cross-feed was ludicrously small.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The belt guard open showing the 4-speed V-belt drive.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

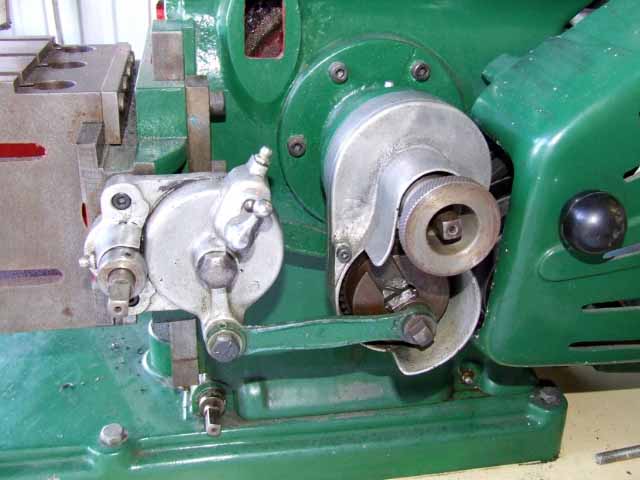

Ram driving mechanism.

The large gear wheel was 1" wide, of 10 d.p. and made from a semi-steel iron. The slotted crank arm was in nickel-chrome-vanadium with a ground finish on its outer surfaces and ground and lapped on the inner "slide" ways. The upper crank pin ran on an Oilite bush with the stroke-positioning screw, crank pin and slide lubricated through a wick oiler contained within the ram clamp screw handle; the lubrication for the slide must have been inadequate for later models had an oil hole drilled through the center of the "slide cover plate". The large "bull" gear was supported by a roller bearing at its near side to absorb the considerable radial loads placed on it and, at the end of its shaft to take thrust loadings, a deep-groove ball race.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

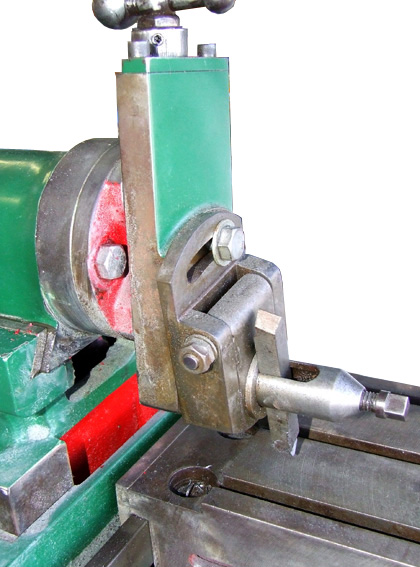

The ram was heavily built and its ways bore on the top, side and bottom

surfaces of the guides - which had oil grooves to hold a supply of lubricant.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cutting rack teeth - indexed, if you are brave, with the micrometer graduated cross-feed screw dial ….

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A box-type casting, the column was braced and ribbed internally and sat on a base strengthened with open ribs. The large bosses for the bull-wheel pinion and crank-lever line shafts were bored and then lined reamed. Later models had a longer base with a machined rectangular block at the front for the table-support screw to slide along.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

External Keyseating - cutting a keyway in

a shaft with a simple square-section tool.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Internal Keyseating - cutting a keyway inside a gear

using a special right-angled Extension Tool.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Another use for the special extension tool - cutting

away the inside of a die block.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Forming a square on the end of a shaft to make a new chuck key - shortly afterwards the one you lost will be found…..

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Finishing a male dovetail on the replacement top slide for the Chinese lathe you wish you'd never bought ….

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Taking the finishing cuts on a pair of home-made V-blocks.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

With the vise base swivelled to the correct angle - and the tool holder tilted - a tapered dovetail can be cut for a fraction of the cost of using a form cutter in a vertical miller.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cutting the base of an over- engineered door wedge.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Clapper head tilted: clearance on back stroke then allows a vertical surface to be is machined without changing the setting used on the top surface.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A jig, held in the regular vise, is given a

finishing cut to its top surface.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The bosses on the bare casting for

a gas engine cylinder are "cleaned up".

|

|

|

|

|

Machining the ways of a lathe saddle casting.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Machining an angle plate bolted directly to

the top of the table with power cross feed engaged.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A job nominally too tall to fit on top

of the table is clamped to the side instead.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

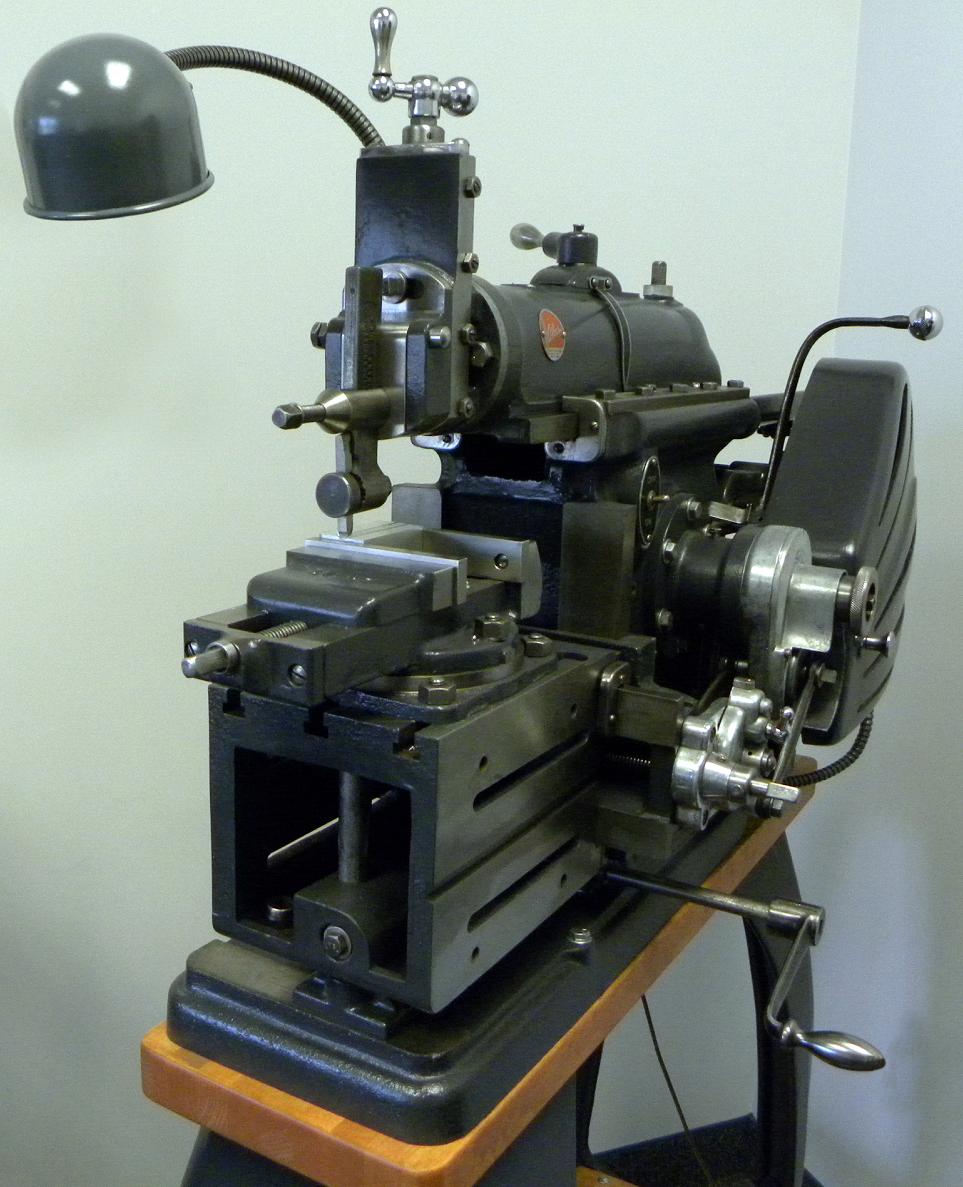

A perfect restoration by Dennis Turk in the USA

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

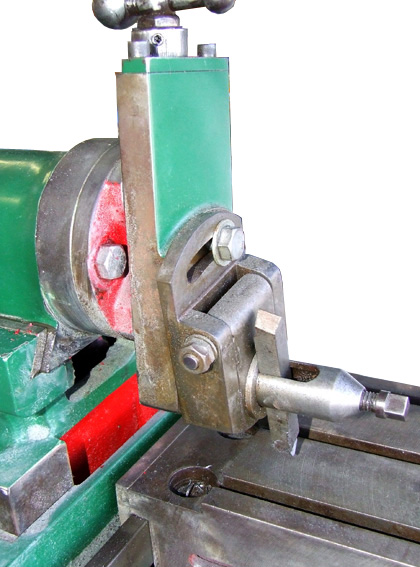

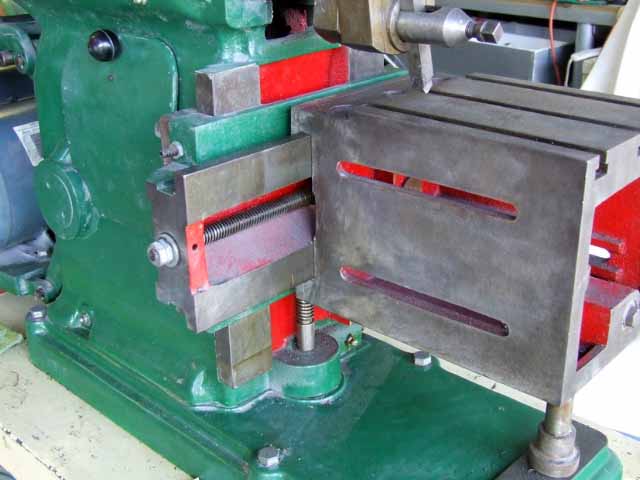

Although the vast majority of Atlas shapers had a ZAMAK housing for their table-drive ratchet mechanism early models used a more robust but expensive-to produce unit in cast iron. Two types were produced - the first had a plunger to select reverse, the second, as shown here, a lever.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|